Water Matters

History of Water Use

Our evolving relationship with Calling Lake

For thousands of years, Calling Lake has been a source of water. Water for fish and water species, including migratory birds and animals, as well as humans who have called Calling Lake home, be it for a season or fulltime, be it for a few or many years.

It seems that the earliest hunters and trappers often came here seasonally, but in the past 200 years folks have come and settled in the community. Some stayed, and many left. The water now serves full-time and part-time residents and guests for a variety of purposes.

Calling Lake is in the Athabasca watershed. If someone were to put a note in a bottle and cork it, that bottle could float into the Arctic Ocean by way of the Mackenzie River Delta at Tuktoyaktuk, NWT.

A corked bottle could also find its way into Calling Lake from other water sources. Rock Island Lake, for example, has an outbound river, Rock Island River, which finds its way into Calling Lake along with a variety of named or no named creeks. Most of these creeks are what we call muskeg fed creeks.

Calling Lake has one exit point for water: the Calling River, which flows out through the low lands at the south end of the lake. It has been said that not too many years ago the Calling River may have exited the Lake closer to Calling Lake Provincial Park. If anyone can verify this claim, we’d like to know.

Calling Lake’s first water treatment plant was built in 1977. A 500-metre water pipeline was installed in the lake in February, and the plant started operating in August 1977. It could treat 21,600 US gallons (81,000 litres) per day.

Ken Sutton worked at the water plant from that first plant’s opening until 2019, first as a contractor and then as a full-time employee. He tells us that a community waterpoint was located on the lot where the Historical Centre now stands, about where the flagpoles are. People would take their buckets and tanks there to access treated water at no charge.

But the waterpoint was prone to failure. So in about 1980, when building the original firehall, the piping for filling the trucks had a public waterpoint added. People could access water from a tap attached to the north side of the firehall. (The firehall later became an Information Centre and is now the Historical Centre.)

With increased usage, the small water treatment plant soon couldn’t keep up with demand. The present water treatment plant was built in 1992 and started operating in December of that year. It could produce 125,000 US gallons (472,000 litres) a day. The original water treatment plant became a workshop for the school.

Water was and still is piped to the core of the community; people living beyond the core get small amounts of water from a coin-operated barrel fill outside the treatment plant. The amount they pay per litre began at about 25 cents per 100 litres and has more than doubled since then. In 2024, a quarter gets you 1.5 minutes of fresh water, pumped into your personal water jugs. That’s about 270 litres of water, charged at $1.75 per cubic metre. There is also a truckfill with a keypad for account holders and municipal trucks needing large quantities, which are metered and billed monthly. The 1992 plant was upgraded in 2022, after 30 years of operation.

Water is hauled on demand to everyone living beyond the core of the community. People sign up to receive water, which was delivered by contract drivers such as Alvin Hershberger, Clarence Cardinal, Brent Peterson and Barry Schmidt until M.D. Opportunity purchased water trucks and hired drivers. As Wilf Brooks puts it, “Now you can sing out for water to be delivered.”

The current system of Water delivery, septic service and garbage pick-up for $50 a month has been in place as far back as 40 Years. Seasonal users are charged a hook-up fee plus the normal $50 for each month they use the service. As cabin owner Trish Bone notes, “This is an amazing, reliable service for all Calling Lake residents and all communities in the Opportunity of MD 17.”

As the saying goes “garbage in garbage out,” which takes us to the waste and sewage side of the waterworks in Calling Lake.

In earlier times, garbage was delivered to a dump site, which moved from place to place. There was little to no supervision or thought of waste separation or recycling. Since the Municipal District of Opportunity was formed in 1995, it has made water, sewer and waste disposal core infrastructure priorities. Those services are now excellent for a community the size of Calling Lake.

In earlier decades, nearly all residents had simple underground waste gathering. Very few had their waste pumped out. As to toilets, all were simple outdoor biffies (outhouses) or inside toilets that dumped into a pit somewhere on the property. More than ideal were located close to the shoreline, or to a creek flowing into Calling Lake. Wilf Brooks recalls that when his family bought a lot along the lake on what became Okow Crescent, its outhouse stood on the beach: “That was the back yard rather than the front for most folks at Calling Lake until cottagers changed that model of thinking, starting in the 1950s.”

To this day, many cottages have an outdoor biffy that is a simple hole dug and perhaps shored up to hold sand from caving in. Often the outhouse holes attract lake water, especially at South Beach where the water table is higher. What affect this has had or is having on our water quality is a question often being asked.

In 1962, Northland School Division put flush toilets in the existing school and ran a pipe from the lake to a concrete cistern in the basement area under one classroom. Bleach was added before the water was used.

Ken Sutton recalls a concern being raised at a community meeting about that pipe, remnants of which were sticking out of the water. If a boat were to ram the pipe, would it affect the water treatment plant? “I assured the individual that the pipe was not in use, having been installed for the school 50 years ago at that time,” Ken says. “I believe shifting ice from breakup had disturbed it, as I recalled seeing it in the water for many years. I went out swimming one day and cut it off with a hacksaw.”

Most property owners these days are using MD-subsidized or self-funded sewage storage tanks that can be pumped out as often as needed for a fee. This one move has made a huge difference in what may be leaching into the lake.

Calling Lake has no cattle or fertilized farmland on its slopes. This is a rare and good thing, as most lakes or waterways in central and southern Alberta have such encumbrances. Unless resource companies in forestry or oil and gas are using any toxic materials that could find their way into the Calling Lake watershed, our lake is remarkably unspoiled.

Ward Chemical, located at the south end of Calling Lake, extracts calcium chloride solution from deep underground in bedrock, something like 1000 meters down. Their business is mainly supplying potash mines with heavy saltwater to suppress groundwater from flooding mines. The water is not from the lake; it has a specific gravity of 1.34 due to minerals contained within.

Much of the water flowing into Calling Lake has gone through at least one filtration system, commonly known as “muskeg.” A simple plant called a bullrush or cattail is another amazing water filtration system, and many other such systems live in the area.

We have no idea what effect clearcutting may have on ground flow into the lake and area streams before new growth begins to absorb moisture from the ground to minimize runoff.

In 1984, a sewage lagoon was built along what is now Hwy 813. The lagoon would be allowed to settle for a year, and then the valve was opened to discharge the water into Two Mile Creek. A new lagoon opened in 2017. It has plastic liners in all sections of the facultative, settling and storage pond. The storage pond (final) was filled in 2022 after five years of collecting. At that time it was released through a pipeline five km to Calling River, downstream from the Lake.

The old lagoon is still in use. It serves the school and surrounding area that has wastewater pipes underground. Trucks transport discharge to the new lagoon from there, rather than releasing into Calling Lake. It is not piped between lagoons because that would have required a creek crossing, which federal fisheries officers opposed due to concerns for spawning fish.

Raw water records of turbidity, colour and temperature, as well as treated water records, are regularly submitted to Alberta Environment. It is a mandatory condition for operating a water plant. Operators are also required to retain records for a significant time.

For many years, volunteers and government officials have been sampling and testing the water of Calling Lake. Local businesses also may have good records of what is coming into our water treatment plant before it is treated and distributed.

The quality of the water coming into our lake when it rains is another question. Wilf Brooks recalls asking the installer of a treatment plant on his Sherwood Park property how clean the water was coming out. “He looked at me and said. ‘Wilf, the water coming out of your sewage treatment plant could be cleaner than the water coming from the sky.’”

Amen

Information provided by Ken Sutton and Wilf Brooks

Below is one community member’s musings on Water Matters at Calling Lake.

Wilf’s thoughts on Water Matters

Wilf Brooks first ventured to Calling Lake in May 1968, when wildfires were scorching the region. His first water experiences in the area involved hauling pails and soaking blankets to help fight the flames – and skiing in a frigid lake. Undeterred by those experiences, he returned often with his wife Shirl Wiselka, who grew up at nearby Big Coulee. In 1973, they joined with Shirl’s twin sister Sylvia and her husband Dave Herbert to purchase a lot on what became Okow Crescent near Two Mile Creek from Ralph Crawford, who had run a fish plant there, and began building the first of several Brooks and Herbert family storage and living quarters.

The main part of the ceremony consists of dancing, typically around four fires, in a clockwise direction and in single file in the wihkohtowikamik, an oblong lodge constructed from multiple conical teepee frames, partially covered with canvas or boughs but open across the top, save a transverse pole. The door faces east or south, with the altar, the area where the drummers sit, opposite. Another fire burns outside the lodge, for those who need a break from the intense ritual or for those who are restricted from entering, such as menstruating women, which is consistent with a range of menstrual taboos in subarctic societies. The lodge is strongly associated with the ceremony, structuring it spatially into more and less sacred zones. The poles themselves have a special significance, as different trees represent community members of different age and sex statuses. The transverse pole with its greenery represents the spiritual leadership of the elder. The lodge represents the community prayerfully coming together to support future generations. In most cases, men and women sit together in families, while in some cases they sit separately….

The ceremony opens with invitational drumming and prayerful invoking of the spirits—generally identified as the spirits of the dead but sometimes as animal spirits—to enter the oblong lodge and share in the feast.

There may be six or eight drummers who take turns playing eight rounds or more. This ceremony can last most of the night or even consecutive nights and often involves multiple meals. It is considered critical that people eat as much food as possible. As not all the food is always consumed during the ritual, the remainder is typically put in the fire, eaten in the morning or covered to be taken home. Mike Beaver emphasizes that the Creator (kihcimanitow) is ultimately the target of the prayers said in his lodge. Prayers could also be directed at animal spirits, to the four directions and to other spiritual grandfathers and grandmothers. Eddie Birdtail referred to this (in response to a question about the role of animals in the ritual during our interview at Trout Lake, October 2013), saying, ‘‘The ceremony is for the animal! They thank the animals, spirits, people who passed on. Like, he [the ceremonialist] invited them.’’ In many such descriptions, the spirits of animals and ancestors, among other entities, appear to be closely associated with one another as beneficiaries of the sacrifice.

The ritual is thus situated in relationship to the environment, not only the terrestrial environment but also the cosmos. …. Like the rituals of the hunter, who disposes respectfully of animal parts and makes burnt offerings, the wihkohtowin exemplifies the reciprocal relationship of spirit gifting (Ghostkeeper 1996). The gift goes beyond the eaters, as the food nourishes absent and deceased kin. The ceremony feeds a collectivity of past and future people while, in some analyses, also welcoming the animal spirits into that community, the commensal domus that is the lodge.

Our Watershed

Calling Lake’s place in the Athabasca Watershed

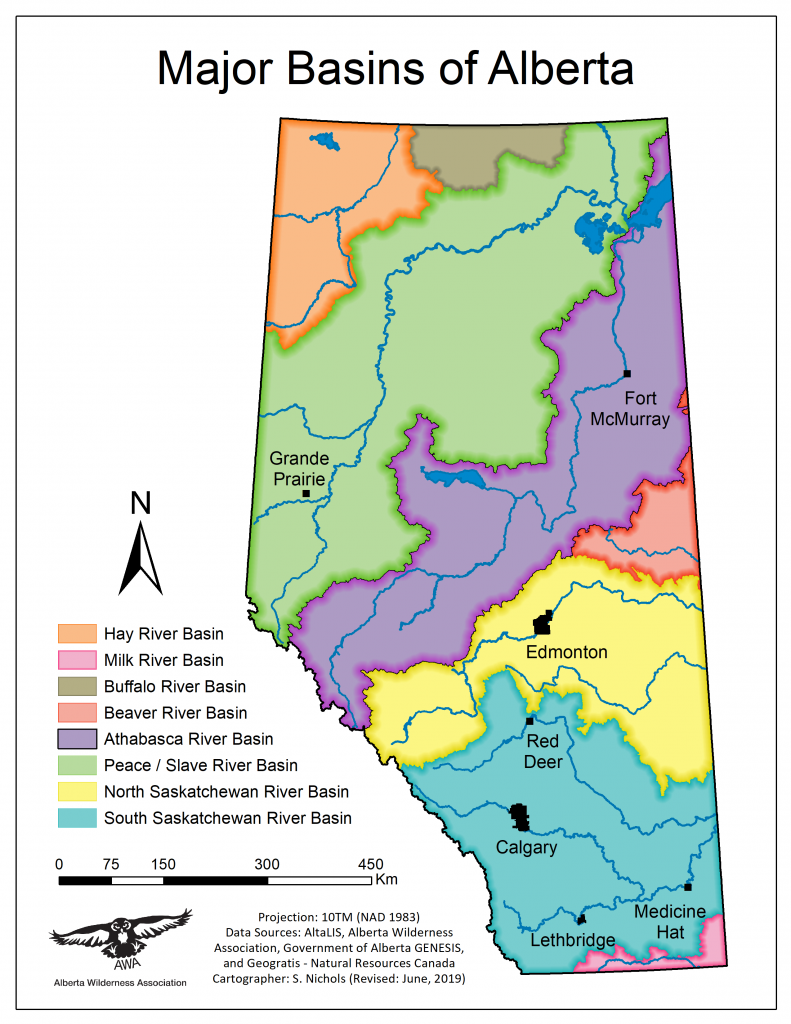

Calling Lake is part of the Athabasca Watershed, which stretches diagonally across the middle of the province.

What is a watershed?

A watershed is an area of land from which rainfall and snowmelt, along with the sediments and dissolved materials they carry, drain into a common water body, such as a river, lake, creek or wetland. The Athabasca Watershed drains into the Athabasca River.

Our river basins are crucial resources that we rely on for drinking water, industry, and recreation. Everything we do on the landscape impacts our water bodies.

Basic information about the Athabasca Watershed

The boundaries of a watershed are determined by the topography of the landscape. Mountains or ridges (like the Rockies) are the natural dividers of watersheds. The Continental Divide is an example of a large ridge that divides river systems that flow into the west (into the Pacific Ocean) from river systems that flow into the east (into the Atlantic or the Arctic Oceans).

Water is everywhere. It’s in lakes, sloughs, and puddles. It’s in rivers, creeks, streams, and underground aquifers. It comes from rain, snow, hail, and melting glaciers. All water flows downhill; if that water eventually ends up in the Athabasca River, then it’s in our watershed. The Calling River flows out of CALLING LAKE to the Athabasca River.

- The area of land draining into the Athabasca River is 159,00 square km.

- The Athabasca River is 1231 km in length.

- Calling Lake has muskeg/wetlands, forested land, several creeks and the Rock Island River flowing into it.

- The Calling River flows out of Calling Lake to the Athabasca River.

Alberta has 7 major watersheds:

- Hay River Watershed

- Peace River Watershed

- Athabasca River Watershed

- Beaver River Watershed

- North Saskatchewan River Watershed

- South Saskatchewan River Watershed

- Milk River Watershed

Healthy lake ecosystems are beneficial for all Albertans. Human use and development are influencing Alberta’s aquatic ecosystems in ways that may not support healthy lake and aquatic life. The Alberta Lake Management Society (ALMS), a charitable society formed in 1991, collaborates with government and other organizations to promote the sustainability of healthy lake and aquatic ecosystems within an ecological framework. Volunteers from Calling Lake collaborate with ALMS to help track the health of our lake.

Another partner of note in stewarding the watershed is the Athabasca Watershed Council. Since August 2009, this not-for-profit has worked collaboratively with the Government of Alberta, Indigenous peoples and others with knowledge to share, providing timely and credible information about the watershed to facilitate informed decision-making.

For more about the importance of watersheds and initiatives to protect them, search theses websites:

- Alberta Environment and Protected Areas: Watershed management

- Athabasca Watershed Council: What is a watershed?

- Athabasca Watershed Council: Understanding the Athabasca Watershed

- Agriculture Canada: Understanding watersheds

Ecological Value

Calling Lake’s essential roles for migratory birds, wildlife, vegetation, local citizens and lake users

Calling Lake is a large (134 km2/52 sq miles), attractive recreational lake noted for its sandy beaches, sport fishing, natural beauty and tranquility. First Peoples here have called it ᑭᑐᐤ ᓵᑲᐦᐃᑲᐣ (Kitow Sâkahikan) or “the lake calls out” in Cree, a nod to the growling moans, loud noises emitted as the ice freezes in the winter, thaws and breaks up each spring.

Located in Alberta’s Municipal District of Opportunity No. 17, the lake is part of Calling Lake Provincial Park, a popular spot on the southern shore of the lake. The Hamlet of Calling Lake and the St Jean Baptiste Gambler 183 First Nation Reserve of the Bigstone Cree Nation are located on the lake’s eastern shore. Bigstone Cree Nation also has reserves at two other communities in Northern Alberta: Chipewyan Lake and Wabasca. The Nation was signatured to Treaty 8 in 1899.

Fishing Calling Lake

Healthy lake ecosystems are beneficial for all Albertans. Human use and development are currently influencing Alberta’s aquatic ecosystems in ways that may not support healthy lake and aquatic ecosystems. Calling Lake plays essential roles for northern Alberta’s migratory birds, wildlife, vegetation, local citizens and lake users.

Forest disturbance, whether by fire, insect or harvest, has consequences for biological communities surrounding Calling Lake. The Calling Lake Fragmentation Study provides insights into how birds respond when a forest is disturbed. This University of Alberta study, sponsored by Al-Pac, Vanderwell and the Government of Alberta, explores how conventional harvest blocks have affected bird communities in this region since 1993. The study’s many findings have expanded our understanding of disturbance, forest patch size, age and connectivity on habitat selection and bird abundance.

For birds, a recently disturbed forest is very different from one that has been growing, uninterrupted for decades. Some species are very picky about this, and others are not choosy at all. The most recent studies have found that some bird species, those most dense in mature forests, start nesting in a harvested patch after about 25 years of regrowth. This tells us that areas of older forest should always be part of the forest mix, so that these bird species have a place to nest as nearby harvested patches regrow. A diverse bird community requires a diverse forest with varying times since disturbance and habitat connections among cut patches.

The quality of lake water is also crucial for ecosystem health. Factors such as nutrient levels, clarity and pollution impact the overall ecosystem. A healthy lake maintains balanced nutrient levels, clear water and minimal pollution. Efforts to reduce nutrient runoff, manage pollutants and protect water sources contribute to maintaining water quality.

A thriving fish habitat is indicative of a healthy lake. Fish rely on suitable spawning grounds, feeding areas and shelter. Preservation of natural shorelines, wetlands and submerged vegetation supports fish populations. Additionally, maintaining natural shorelines, water temperature, oxygen levels and water flow ensures a conducive environment for fish.

Calling Lake volunteers work alongside the Alberta Lake Management Society (ALMS), in collaboration with government and other organizations to promote the sustainability of healthy lake and aquatic ecosystems within an ecological framework. To find out more about our collaboration with ALMS, see Tracking Lake Health; to learn about volunteering, see Get Involved.

Fishing Calling Lake

Calling Lake in northern Alberta is a fantastic spot for sport fishing, and a recreational destination. The lake has a sandy shoreline and easy access, with three public boat launches – two at the Calling Lake Provincial Campsite and one at Ben Auger Memorial Park. The main sport fish include northern pike, burbot and walleye.

- Species of fish in Calling Lake:

- Northern Pike

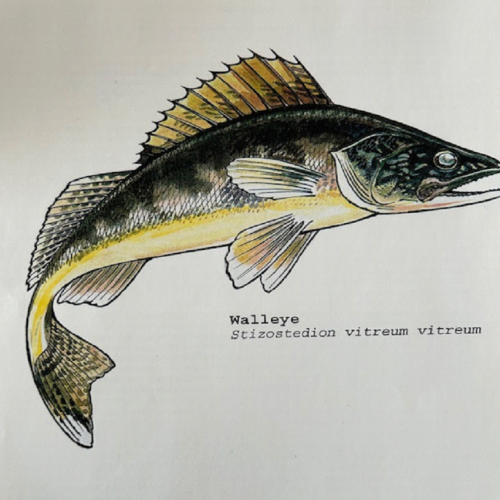

- Walleye

- Burbot

- Whitefish

- Yellow Perch

For more about these species and others, see Alberta game fish species in Alberta Environment’s Fisheries Management section.

Be mindful of Alberta provincial regulations for fish quotas:

- Calling Lake – NB1 (Open June 1 to March 31):

- Walleye: 1 fish (45-50 cm)

- Northern Pike: No fish allowed

- Yellow Perch: 15 fish

- Lake Whitefish: 10 fish

- Burbot: 10 fish

Fishing regulations are subject to change. For updated regulations:

Walleye (Sander vitreus)

Named for their big eyes, walleye are the largest members of the perch family. Two distinct fins are present on the back, the first featuring large spines. A white underside is also characteristic of this fish. In Alberta, walleye are often incorrectly called “pickerel,” but that is the accepted common name for some members of the pike family in eastern Canada.

Northern Pike (Esox lucius)

Sometimes called jackfish, northern pike are long, slender fish with sharp, backward-slanting teeth, duck-like jaws and a long, flat head.

Whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis)

Lake whitefish are olive-green to blue on the back, with silvery sides. They have a small mouth below a rounded snout, and a deeply forked tail.

Yellow Perch (Perca flavescens)

A yellow perch typically has a golden yellow or green body with broad, dark vertical bands on the side. They have needle-like spines on the dorsal fin.

Burbot (Lota lota)

Also known as freshwater cod or ling, burbot are found in lakes and streams throughout most of Alberta. These unusual-looking fish have a slim, brownish black body with smooth skin and a flattened head.

Tracking Lake Health

Alberta Lake Management Society

The Alberta Lake Management Society (ALMS) was formally established November 1991 to promote understanding and comprehensive management of lakes and reservoirs and their watersheds. The society incorporated as a non-profit organization under the Societies Act of Alberta in December 1991 and the following year became the first Canadian Chapter of the North American Lake Management Society (NALMS). In October of 2001, the Government of Canada granted ALMS its “Charitable Organization” status.

Besides collecting and interpreting water quality data on Alberta lakes, ALMS educates lake users about their aquatic environment, encourages public involvement in lake management and facilitates cooperation and partnerships.

ALMS and its members play an active role in linking lake users, local communities, educational institutions, governments and industry in the common goal of lake and watershed management. It strives to increase public understanding of the importance of lakes and their watersheds through initiatives such as these:

- Facilitating workshops;

- Offering courses, seminars, conferences and meetings;

- Collecting and disseminating information about lakes and lake management;

- Providing occasional scholarships and bursaries for education that fosters research or advances knowledge in aquatic sciences;

- Helping to develop local, provincial and national programs that promote lake and watershed management and/or encourage the protection of lakes and watersheds;

- Providing expertise to and collaborating with other organizations, agencies and individuals concerned with lakes and lake and watershed conservation and improvement.

Community involvement in ALMS

Calling Lake participates in several sampling programs through ALMS, thanks to the dedication of local volunteers. For youngsters as well as older folks, it’s a wonderful way to be on the water while doing a good thing. Besides taking samples during the winter and every second summer, volunteers respond to requests for additional sampling to inform academic and government research. Volunteers who take ALMS staff out to do lake sampling provide the boats, gas and time. 10 locations are ideally sampled in the lake for a variety of parameters. For more about those parameters, click on the following links:

LakeWatch

Developed under the umbrella of ALMS, LakeWatch is a volunteer-based monitoring program in which local citizens team up with an ALMS employee to gather water samples from lakes in Alberta. ALMS technicians assist volunteers to test the lakes four times during the summer, collecting important data about water temperature, clarity, a suite of water chemistry parameters, invasive species and other biological targets. Once the data is collected, ALMS shares it with Alberta Environment and produces LakeWatch reports summarizing the data for each lake in an easy-to-understand manner. The data is used to educate lake users and to guide water restoration and management efforts.

The volunteer program empowers local citizens to become active in their own lake and community and gives them ways to understand and have a positive impact on the future of their lake. There is no better way for residents to take an active role in monitoring the water quality in their own backyards.

To find out more, contact programs@alms.ca or check out the LakeWatch Volunteer page.

LakeWatch reports

Thanks to the partnership between local volunteers and ALMS, LakeWatch reports on the health of Calling Lake are available for the following years. Click on a year to open the corresponding report: 2000 2001 2010 2011 2017 2018 2019 2021

Our shared goal is to capture enough research and data about our lake to answer community questions now and in the future. Questions such as the following:

- How has the lake changed over time with the impacts of industry, new lagoons, settlement, and activities on and around the lake?

- Are algae blooms the same, worse or better than the past?

- How do the blooms compare to other Alberta lakes?

- Are winter conditions changing on the lake?

Please refer to www.alms.ca for answers to the above questions and any others you may have. All the data collected is available for public access, and ALMS staff are always willing to help community members understand its significance.

Some helpful definitions regarding water quality:

Hypereutrophic – extremely rich in nutrients and minerals;

Eutrophic – rich in organic and mineral nutrients, supporting abundant plant life, which in the process of decaying depletes oxygen levels and animal life;

Mesotrophic – low oxygen levels and fair water quality;

Oligotrophic – least amount of biological productivity, good water;

Secchi depth – the depth at which there is enough light for photosynthesis, the easiest and most widely used measure of lake water clarity. Water quality is influenced by suspended materials both living and dead, as well as dissolved coloured compounds in the water column. Lakes are usually clearer in late spring, then become turbid (cloudy) with increased algae growth as the summer progresses.

You will find this information and much more on the ALMS website. Under “Programs,” click on “LakeWatch,” then “LakeWatch Reports,” then scroll down to “Individual Lake Reports” to find Calling Lake. Here you will find reports about our lake’s water quality, water chemistry, clarity and euphotic depth, temperature and dissolved oxygen, invasive species, water levels and more. Plus analysis of trends over time.

The future of water sampling will be influenced by government funding, volunteer energy and the need to share resources among all Alberta Lakes. It’s our hope that the volunteer lake monitoring program will continue, and that data will be used by future stewards of Calling Lake to make the best decisions for the health of this lake.

Recent analysis of Calling Lake

The following excerpt from the LakeWatch Report for 2021 provides a snapshot of findings regarding the health of Calling Lake.

Calling Lake Calling Lake is considered dimictic, a term describing lakes that stratify and mix twice per year. During early spring, surface waters warm from 0° C and eventually reach the same temperature as deeper waters (around 4° C). This period of uniform temperature induces a spring mixing event often referred to as spring turnover.

Stratification was apparent at 5 m by June and slowly moved downward through the summer to 8 m. Isothermal conditions were restored by September. Dissolved oxygen concentrations declined below the thermocline, particularly below 8 m. At the end of July, surface waters also became saturated in dissolved oxygen, likely as a result of algal growth.

Calling Lake is eutrophic according to mean summer phosphorus, chlorophyll and transparency criteria. Eutrophic lakes are common in Alberta and are distinguished by high algal growth and low water clarity. Occasionally, algal growth may reach nuisance levels and detract from recreational aesthetics of this lake.

Total phosphorus concentrations averaged 55 µg•L -1, similar to values recorded in 1988. Total phosphorus was at its highest during the late summer, corresponding to peak algal growth.

Total nitrogen averaged 656 µg•L -1 and increased gradually from a July low through the summer. TN:TP (nitrogen to phosphorus) ratios averaged 14 and only dropped below 10 in September.

Chlorophyll concentrations were low during the spring and through to mid-July, given the amount of phosphorus available during the same period. Algal growth accelerated by mid-July, likely corresponding to warming of the lake, the development of a thermocline and reduced vertical mixing of water. By mid-August, algal growth produced a large quantity of chlorophyll and likely a doubling algal biomass in the lake. To residents, this would have appeared as a large decline in water quality as Calling Lake switched from mesotrophic to hypereutrophic over a two- to three-week period. While this change from clear to green water would have been dramatic, it was well within expected natural nutrient and chlorophyll parameters for the lake and does not necessarily represent recent pollution.

Major ion concentrations did not fluctuate appreciably through the summer but were low for a eutrophic lake. Mean values for calcium (22 mg•L -1), magnesium (6 mg•L -1), sodium (5 mg•L -1), and potassium (2 mg•L -1) were identical to those reported for 1988 in the Atlas of Alberta Lakes.

Sulfate concentrations were low (3.6 mg•L -1) and consistent with concentrations of other ions.

Total alkalinity, a measure of the ability for a lake to neutralize acidity, was 84 mg•L -1 . The low ion concentrations are likely a result of the extensive wetlands in the drainage basin.

Winter LakeKeepers

Calling Lake volunteers also participate in Winter LakeKeepers, an ALMS program that equips volunteers to independently monitor lakes or reservoirs during the winter. This initiative collects data important for understanding lake ecology and health in cold weather conditions. Whether you’re an avid ice fisher or simply interested in contributing, you can participate in Winter LakeKeepers.

Here’s how it works:

- ALMS provides training manuals and monitoring equipment to Winter LakeKeepers volunteers. Equipment provided includes the following:

- YSI ProODO dissolved oxygen and temperature probe (20m or 30m long)

- Nutrient sample bottles

- Phytoplankton (algae) sample bottle

- Isotopes sample bottle

- Routine chemistry sample bottle

- Chlorophyll-a sample bottle

- Chlorophyll-a filtering kit

- Field sheets

- Instruction guide

- Sampling gloves

- Sample preservatives

- Tape and weight

- Volunteers collect data from lakes or reservoirs using the provided equipment and deliver the samples to the ALMS office in Edmonton for analysis and reporting. Two protocols are available:

- Base-Level Protocol allows more time to deliver samples back to ALMS.

- Enhanced Protocol collects additional samples that require quicker delivery to ALMS

- Data and field sheet information are uploaded to a water quality data portal and used to compile reports for each season. These reports are available here.

To volunteer with Winter LakeKeepers, contact ALMS at programs@alms.ca or call 780-702-2567. By participating, volunteers contribute valuable data that enhances our understanding of lake ecosystems during the winter months.

Calling Lake volunteers have been participating in Winter LakeKeepers for three years. In 2023, for example, Owen and Tamara Larson took lake samples through the ice to study lake hypoxia, cyanobacteria conditions, water temperatures, phosphorus and other measures in the Athabasca River and Lesser Slave Lake watersheds.

Click here for a recent report based on winter lake sampling.

Algal blooms

Many Calling Lake users are concerned about potential toxicity caused by blue-green algal blooms and wonder what those blooms may mean for water recreation safety as well as the overall health of the lake. There are records of algal blooms in Calling Lake since 1978, and long-term residents tell stories of blooms back in the early 1900s.

Although this is not a new problem, current human activities that increase the movement of nutrients into the water, such as use of fertilizers and wastewater effluent, have the potential to increase the severity and frequency of the blooms. It is important to continue collecting data so we can compare and make ecological changes if the blooms are more frequent and last longer than in the past. Good watershed management is key to limiting the growth of the blooms.

What are algal blooms?

Every year during the warmer summer months, Alberta lakes undergo visible changes to water clarity. The clear transparent water may suddenly take on a soupy appearance and turn blue-green, bright blue, grey or tan. The organisms responsible for these changes are photosynthetic bacteria called cyanobacteria. They share many similarities in overall appearance, habitat and nutrient requirements with algae, and thus were originally misclassified as algae. In fact, many people still refer to them as blue-green algae, and their accumulation at the water’s surface as a blue-green algae bloom.

Alberta lakes are home to more than 100 species of cyanobacteria, ranging from tiny cells invisible to the naked eye to larger colonies that look like fine grass clippings, small shapeless clumps or a homogeneous soupy mass. The most troublesome blooms in central and northern Alberta lakes are caused by three species of Blue-Green algae: Aphanizomenon flos-aquae, Microcystis aeruginosa and Anabaena Flos-aquae. Bright blue and blue green in colour, these blooms appear during hot, calm weather. The algal cells contain small gas bubbles that cause them to rise to the surface of the lake and accumulate a scum. Wind and wave action concentrates scums on the shoreline and in bays, where they begin to decompose, causing a foul odour.

Toxicity concerns

Blue-green algae have been known to be a cause of toxicity in lakes, ponds and dugouts for more than 100 years, when the first poisoning cases were recorded. Cyanobacterial toxins are the naturally produced chemicals stored in the cells of certain species of cyanobacteria. When the bacteria die and decay, the toxins may be released into the water, posing a health risk to waterfowl, wildlife, domestic animals and of course humans. Although certain toxins may persist in the water at low levels for many months, most will in degrade in the sunlight within two weeks.

These toxins fall into various categories depending on which part of the body they affect. Some are known to attack the liver (hepatotoxins), others the nervous system (neurotoxins), while some simply irritate the skin. Hepatotoxins are the most widespread and frequently occurring toxins produced by cyanobacteria, which is why officials are most concerned with health risks associated with these types of toxins. Nerve toxins are rare but have been linked to periodic losses of livestock, pets and wildlife.

The amount of toxin produced varies over time and from lake to lake. A cyanobacterial bloom may produce very little or no toxin in one lake and a later bloom in the same lake could produce a large toxin concentration. Unfortunately, no known method exists for predicting the toxin content of a cyanobacterial bloom. Not all types of cyanobacteria produce toxins, but it’s not possible to tell if a bloom is harmful based on how it looks. Thus all cyanobacterial blooms must be treated with caution.

Symptoms of contact with cyanobacterial toxin

The following symptoms may appear within one to three hours of contact with a blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) bloom. Symptoms in children are often more pronounced; however, all humans are at risk. Below are some common symptoms named in a useful Alberta Health Services FAQ:

Contact Exposure

- skin irritation and rash

- sore throat

- sore, red eyes

- swelling of the lips

- hay fever symptoms (e.g., stuffy nose)

Consumption of blue-green algae (cyanobacteria)-contaminated water

- headache

- diarrhea

- weakness

- liver damage

- fever (temperature over 38.5 °C or 101.3 °F)

- nausea and vomiting

- muscle and joint pain

- abdominal cramps

What causes the blooms?

Cyanobacteria are well adapted to grow in Alberta’s nutrient rich lakes, ponds, and reservoirs. They can out-compete algae for optimal levels of sunlight and nutrients, in part by regulating their buoyancy in the water column. Unfortunately, cyanobacteria sometimes become over-buoyant and concentrate near the surface, especially when calm conditions follow windy periods. Surface accumulations may intensify when waves concentrate the bacteria in bays or along shorelines and beaches, resulting in blooms that may appear as brightly coloured slicks or scums on the surface of the water.

In Alberta, blooms are most common from early July to mid-September. A typical bloom will last two to three weeks before it dies and decays. In some extremely nutrient rich lakes, cyanobacteria can persist throughout the whole summer and into the fall, with several species dominating the open water in succession.

Precautions you can take

- Treat all intense blooms with suspicion.

- Do not drink water from bloom-infested lakes and reservoirs.

- Do not swim, wade or play in water with concentrated algal material.

- Watch children carefully and keep them out of water with concentrated blooms.

- Provide alternate sources of drinking water for domestic animals and pets.

- Please report suspected blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) bloom in Calling Lake to the local AHS Environmental Public Health Office by calling 1-833-476-4743.

- If you have been exposed to a blue-green bloom, shower promptly with clean tap water. If symptoms develop, contact Health Link Alberta at 811.

For more information, contact Alberta Health Services, Alberta Environmental Monitoring or Alberta Environment and Protected Areas.

You can help prevent blue-green blooms

The best way to help prevent cyanobacterial growth is through good watershed management and reducing nutrient loading in lakes and ponds. You can limit the amount of nutrients entering the system by not using lawn fertilizers, properly maintaining private sewage systems and maintaining a buffer of natural vegetation around water bodies to filter the incoming water. In addition, consider getting involved as a lake monitoring volunteer.

People and communities working for sustainable lakes in Alberta!

For more information:

ALMS – Cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) and their Toxins

Alberta Health Services – Cyanobacteria FAQ

Get Involved

Information Coming Soon

Land Acknowledgement

Recognizing that we are all equally responsible to know our shared history and journey forward in good faith, we acknowledge with respect that Calling Lake stands on land, and alongside water, where Indigenous peoples have gathered, hunted, fished and held ceremonies from time immemorial.