Indigenous History

Content

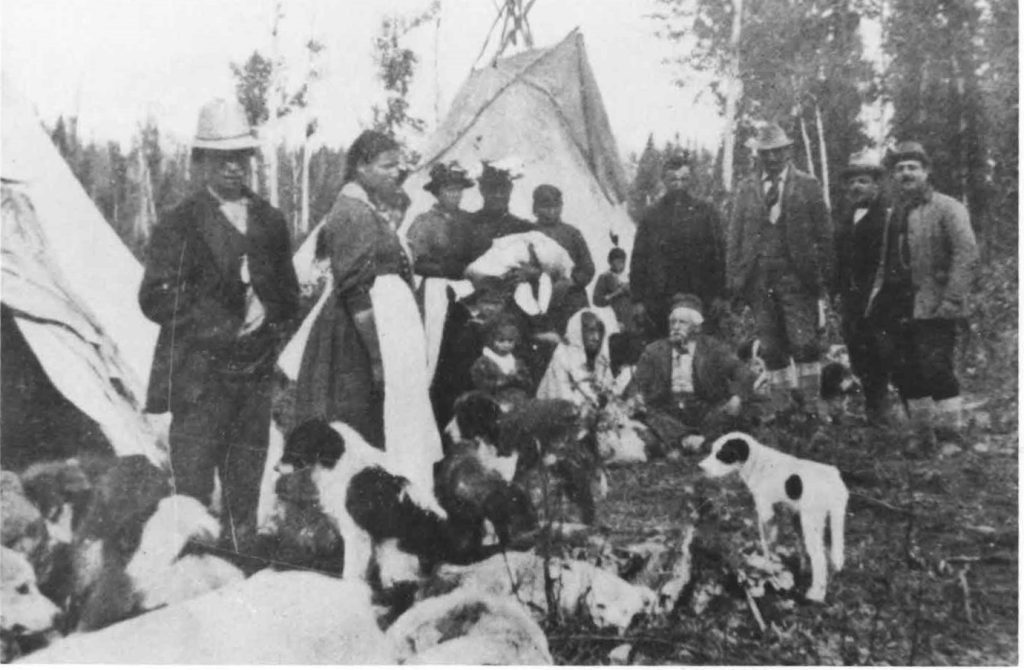

Indigenous people in their oral tradition say they have been on this land from time immemorial. Elders here describe a migration pattern that brought people to Calling Lake for a time each year to benefit from the bounty of fish before moving a bit north to Rock Island Lake to hunt. Later, Indigenous peoples were the first humans to live here year round. We have much to learn about their stories over time.

Studies along the lakeshore in the 1960s by Dr. Ruth Gruhn of the University of Alberta help to confirm oral histories, finding evidence of seasonal hunting or fishing camps at sites near the Calling River, on property owned by Ken Sutton and elsewhere. Those artifacts were dated back to 3000 BC, possibly before. Discoveries here and elsewhere raise intriguing questions about the lives and journeys of the region’s Indigenous ancestors.

In the 1400s, far away and without consulting Indigenous peoples, papal bulls claimed legal title to any land not occupied by Christians in the so-called new world. Those “Doctrines of Discovery” set the stage for an influx of fur traders, missionaries, settlers and legislation that drastically changed life for Indigenous peoples of “turtle island,” including those with ties to Calling Lake. (Later popes revoked the decrees but heavy-handed colonization continued.)

By the late 1700s, fur traders had opened posts in what is now northern Alberta, beginning with Fort Chipewyan in 1788. In this region, as elsewhere, Indigenous people shared their knowledge of travel routes, food sources and natural cures even as European diseases such as smallpox claimed thousands.

Indigenous people from communities such as Lac La Biche regularly came to Calling Lake to hunt and fish, but it seems there was no permanent habitation until the mid-1800s, when some families began moving here, drawing from the abundance of fish, fowl and furs to meet their needs.

Meanwhile, the Dominion of Canada formed in 1867 and assumed responsibility for “Indians and lands reserved for Indians.” Intending to open vast territories to settlers, the government proposed treaties exchanging Indigenous land rights for a system of reserves (treaty lands), cash payments, access to agricultural tools, and hunting and fishing rights. Eleven treaties are signed. The treaty applying to this region, Treaty 8, was signed June 21, 1898 at Lesser Slave Lake; the Bigstone people most predominant here adhered at Wabasca two months later, on August 14. A Half-Breed Scrip Commission also traveled the territory, offering scrip to Métis people with similar intent. Local Métis people gathered at the mouth of the Calling River Sept. 14, 1899 to meet the commission.

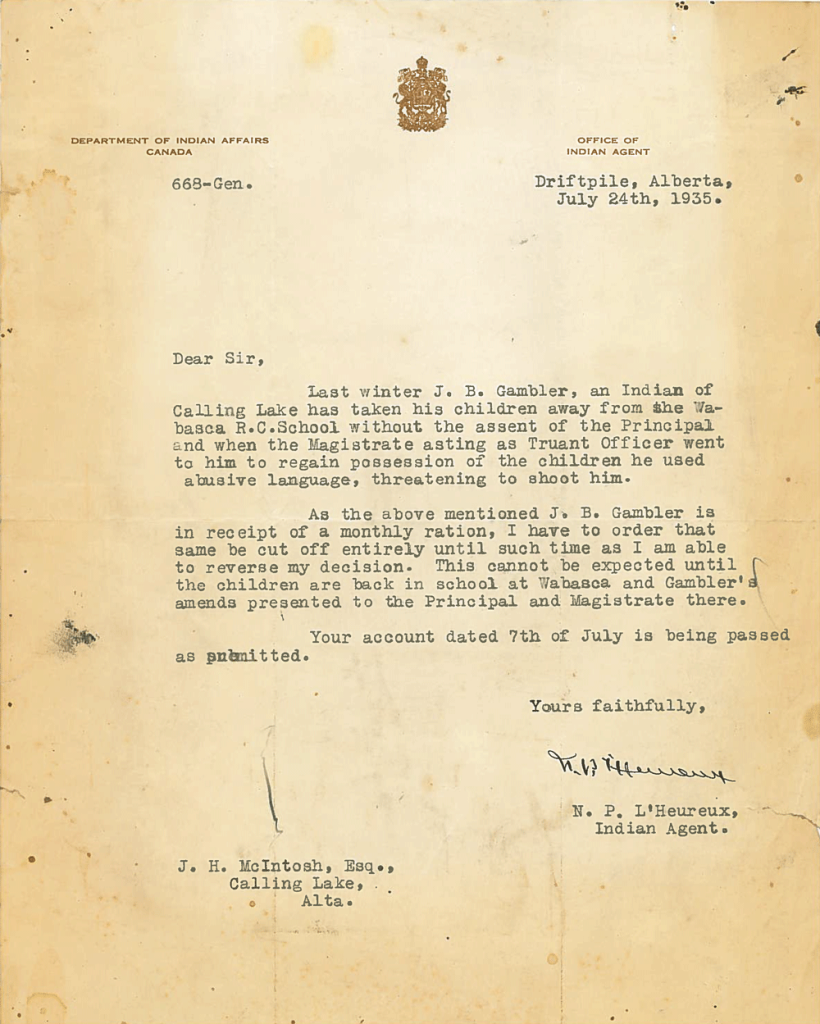

Growing government restrictions on Indigenous ways of life came to include compulsory attendance at residential schools. Some Calling Lake children were taken to Wabasca for schooling; at least one family refused and was threatened with losing other benefits as a result.

The Jean Baptiste Gambler Reserve, which lies at the north end of the Calling Lake community, came into being in 1919. The one-square-mile reserve was set apart in Severalty by Order in Council for use by the Jean Baptiste Gambler family. The reserve has since become part of the Bigstone Cree Nation headquartered in Wabasca.

Nearly a century later, in 2010, the Bigstone Cree Nation settled a federal land claim that promised 40 square miles of additional TLE (Treaty Land Entitlement) at four new locations: across Calling Lake to the south and north, at Rock Island and along the Calling River.

Voices of the Land

Interviews with Indigenous residents from Calling Lake

As part of local heritage initiatives, a team from the Municipal District of Opportunity No.17 recorded oral histories with Indigenous residents of Calling Lake. Short videos featuring the following people are available online at Voices of the Land, within a section devoted to the MD of Opportunity #17

The MD Opportunity No.17 Library Board continued work on the project, arranging interviews of Indigenous residents (mostly Elders) in Wabasca, Red Earth Creek, Lake Chipewyan, Trout Lake, Sandy Lake and Peerless Lake. The production company involved, Lindisfarne Productions, also edited and added footage to the existing Calling Lake videos. In this way the Library Board supported the original aim of the MD to educate and preserve community history while also supporting the Public Library Services Branch Indigenous Outreach program. These videos offer a compelling snapshot of some of the people who made these communities vibrant.

Voices from other communities in MD of Opportunity 17

- Ida Yellowknee, Wabasca

- Ida Ruth Houle, Peerless Lake

- Dollie Anderson, Red Earth Creek

Local archaeological findings

An archaeological survey of Calling Lake led by Dr. Ruth Gruhn of the University of Alberta unearthed “an abundance of prehistoric material” whose styles suggest human occupation as far back as 3000 BC. Her team excavated four prehistoric campsites on the east and southeast shore between 1966 and 1968, turning up microblades, projectile points, bifaces, scrapers and heavy tools. Most objects could be linked with cultures of the northern boreal forest, although projectile point styles suggest affiliations with Plains traditions in the south.

Dr. Gruhn’s interest in Calling Lake as a place to explore earlier Boreal Forest cultures was sparked by a report by Fred Broadbent, a member of the Archaeological Society of Alberta, on materials found east of his summer cabin on the east shore of the lake. A preliminary survey by Drs. Gruhn and Alan Bryan in 1965 recorded several other sites, and Dr. Gruhn’s work identified seven, including one owned by Ken Sutton. Most of the sites are near the mouth of small streams or on sand ridges.

Summary of Dr. Gruhn’s research at Calling Lake

Digging into the Past

Bo Emery recalls boyhood days at Calling Lake

Land Acknowledgement

Recognizing that we are all equally responsible to know our shared history and journey forward in good faith, we acknowledge with respect that Calling Lake stands on land, and alongside water, where Indigenous peoples have gathered, hunted, fished and held ceremonies from time immemorial.