Forestry

Content

Related Documents

Excerpted from Calling Lake Spirit, Vol. 10, June 2023 Courtesy of the Forest History Association of Alberta

The forests around Calling Lake began to form following the last ice age 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. Early inhabitants of the forest were Indigenous hunters and gatherers, living on and with the land. There is evidence that they also managed their environment using fire to clear certain forest areas for ease of travel and to encourage the plants and animals on which they depended for life. Those early inhabitants were also the first “loggers” of the forest, using the trees for cooking and warming fires, and for shelter. (Alberta Forest Service 1930-2005: Protection and Management of Alberta’s Forests; Page 2)

Shaped by wildfires in the late 1880s, the forests of today are a mix of white spruce, black spruce, jack pine, aspen and poplar trees. Early residents of Calling Lake and area used the forest for hunting, gathering, and building houses, sheds, barns and fences. The first buildings were constructed with logs; later, with lumber sawn and hewed by hand with cross-cut saws and adzes.

Logging and Sawmilling

Situated on the Athabasca River, Athabasca Landing had an active timber industry in the late 1800s and early 1900s. With the river as the main travel corridor, sawmills, planer mills and other companies were set up to built boats and scows, provide cordwood to steamboats and create lumber for construction up and down river. Logging was done in the forests along the river, with the logs floated down the river or hauled by horse-drawn sleighs to the mills. In the May 9, 1913 Northern News, the Athabasca Lumber and Supply Company Ltd. ran an advertisement selling lumber, informing farmers in the area of their species and costs. Fir brands were $23 per thousand, cedar shiplap was $25 per thousand, No. 2 shingles were $2.65 per thousand, and rough lumber for cribbing wells was $23 per thousand. (Reflections From Across The River, A History of the Area North of Athabasca, 1994)

Chester Day at his log house in Calling Lake, 1930s; Evergreen 1966-67

Mr. and Mrs. Samuelson at their log house west side of Calling Lake, 1933; Evergreen 1966-67

Bob Logan building the Calling Lake Health Centre with logs and lumber, 1956; Evergreen 1966-67

Although Calling Lake was more isolated in the early 1900s, the settlers required the forests to supply firewood and shelter. Buildings were made with logs or lumber cut on site or brought in on the bush roads from the south. Mrs. Caroline Gambler recalls Peter Gambler making his own lumber when he built his first house. “It was very hard work for two men to cut the lumber by hand with a saw. The roof was of poles with strips of birch bark laid on top. The birch bark was covered with dirt. The roof did not leak.” (Evergreen, 1966-67; Page 14) Other documented “firsts” include Jim McIntosh owning the first steam engine to power his sawmill to cut lumber, and Nick Tanasiuk building a shingle splitting machine and later a sawmill at their farm at Rock Island Lake. (Evergreen, 1966-67)

Arch truck hauling logs to sawmill landing; February 1962; Photo: Rudy Wiselka

Alberta Pacific Forest Industries (Al-Pac) opened a huge pulp mill in 1992, and new access was built to Calling Lake for their deciduous timber operations. Double R Forest Products was sold to Tara Forest Products in 1992, and both Tara and Crawford coniferous timber quotas were sold to Vanderwell Contractors in the late 1990s. Both Vanderwell and Al-Pac continue to operate in the Calling Lake area.

Paul Wallach: Logging and planing on the farm

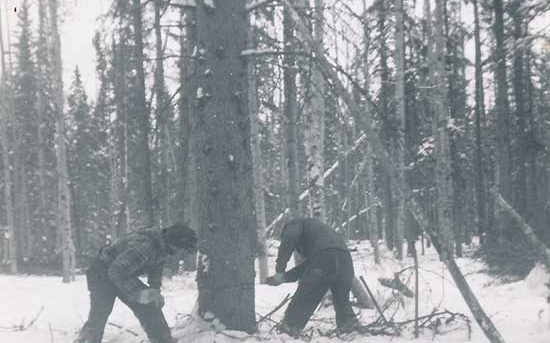

Two of Paul Wallach's fallers using a cross-cut saw to fell a white spruce tree. Calling Lake area, 1948. Photo: Brian Wallach

Two of Paul Wallach's fallers using a cross-cut saw to fell a white spruce tree. Calling Lake area, 1948. Photo: Brian Wallach Paul Wallach setting up his planer to plane rough lumber. This was one of the first planers he owned. Athabasca area, 1954

Paul Wallach setting up his planer to plane rough lumber. This was one of the first planers he owned. Athabasca area, 1954 Paul Wallach standing in front of the first truck he purchased for hauling lumber from his sawmill site. Calling Lake area, 1948

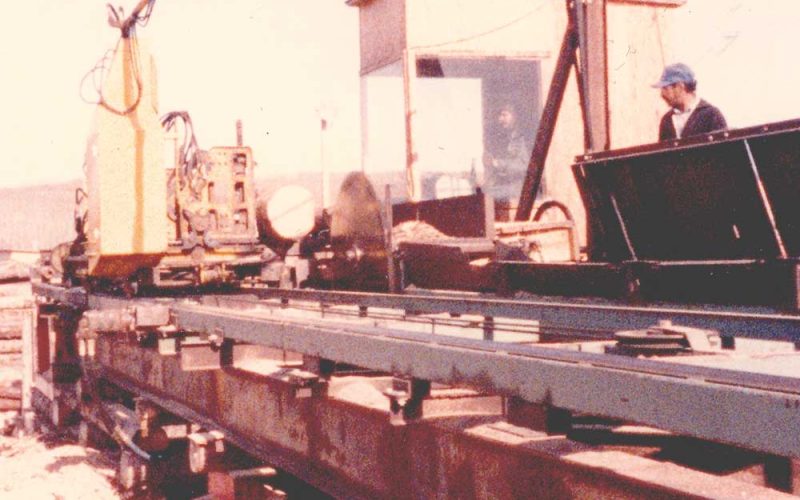

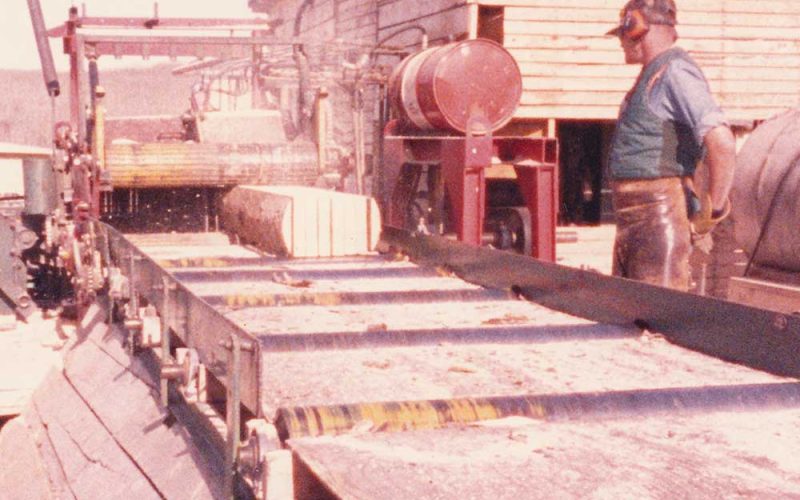

Paul Wallach standing in front of the first truck he purchased for hauling lumber from his sawmill site. Calling Lake area, 1948 Head saw on the Paul Wallach sawmill. Wabasca area, 1970s

Head saw on the Paul Wallach sawmill. Wabasca area, 1970s An unidentified worker standing in front of Paul Wallach's headsaw, edger and power unit. Calling Lake area, 1948

An unidentified worker standing in front of Paul Wallach's headsaw, edger and power unit. Calling Lake area, 1948 Paul Wallach with a load of planed or “dressed” lumber at his summer planing yard, ready for delivery to Edmonton. Athabasca area, August 1975

Paul Wallach with a load of planed or “dressed” lumber at his summer planing yard, ready for delivery to Edmonton. Athabasca area, August 1975 Paul Wallach custom planing rough lumber for another sawmiller in the Athabasca area, summer, mid-1950s

Paul Wallach custom planing rough lumber for another sawmiller in the Athabasca area, summer, mid-1950s Paul Wallach sawing logs at the headsaw “at the stick,” assisted by canter Alex Makar on his left. Calling Lake area, 1948

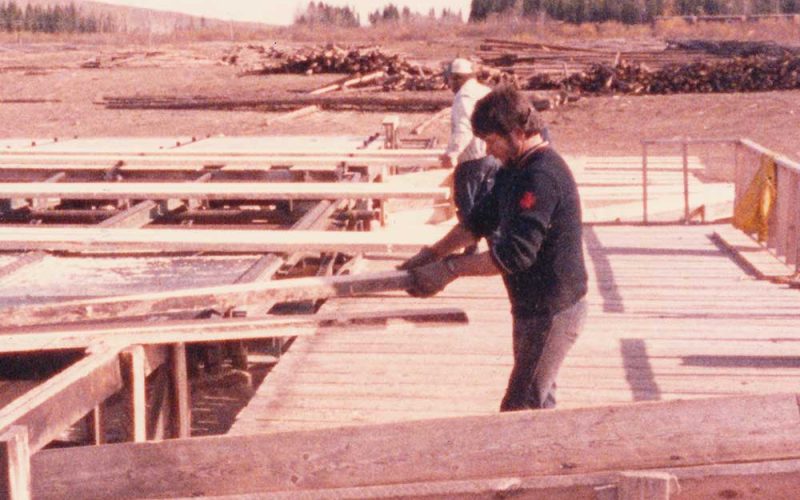

Paul Wallach sawing logs at the headsaw “at the stick,” assisted by canter Alex Makar on his left. Calling Lake area, 1948 Sorting sawn lumber on the green chain at Paul Wallach’s sawmill. Wabasca area, 1970s

Sorting sawn lumber on the green chain at Paul Wallach’s sawmill. Wabasca area, 1970s Sawing 2x8s or 2x10s at the Paul Wallach sawmill. Wabasca area, 1970s

Sawing 2x8s or 2x10s at the Paul Wallach sawmill. Wabasca area, 1970s Rough lumber being loaded by hand onto Paul Wallach's lumber truck. Calling Lake area, 1948

Rough lumber being loaded by hand onto Paul Wallach's lumber truck. Calling Lake area, 1948 Rough lumber hauled during the winter from Paul Wallach's sawmill in the Calling Lake area to his yard southeast of Athabasca, where it is stacked for planing later that spring and summer. Athabasca area, April 1961

Rough lumber hauled during the winter from Paul Wallach's sawmill in the Calling Lake area to his yard southeast of Athabasca, where it is stacked for planing later that spring and summer. Athabasca area, April 1961 Some of Paul Wallach's sawmill crew, including his wife Anne, the camp cook. Calling Lake area, 1948

Some of Paul Wallach's sawmill crew, including his wife Anne, the camp cook. Calling Lake area, 1948

Alberta Forest Service

With the energy boom of the late 1940s, the Alberta Forest Service began investing in wildfire and forest management in the northern parts of Alberta. The Lac La Biche Forest Division was created in 1955, and Calling Lake became part of this new division, along with Wandering River, Beaver Lake and La Corey. Until the 1950s and 1960s, the rangers were also game guardians, combining fish and wildlife work with their wildfire and timber work.

Many of the early fire or forest rangers were located around Athabasca and travelled to Calling Lake on horse, foot or dogsled. Names from the past include Axel Smith, Charlie Carter, Gisli Gislason, Ludwig Silver (1941–1944) and William (Bill) McPherson.

In 1949, Bill McPherson became the first ranger to be stationed in Calling Lake. He had moved to the area in 1938, homesteading just south of Frank Crawford’s place. Bill retired in 1961, and Ernie Stroebel took over as Chief Ranger. Houses for the rangers were built in the late 1950, early 1960s. Following Ernie, Chief Rangers included Dennis Howells (1964), Ray Olsson (1976), Glen MacPherson (1980), Rick Stewart (1982), Don Pope (1987), and Don Podlubny (1991).

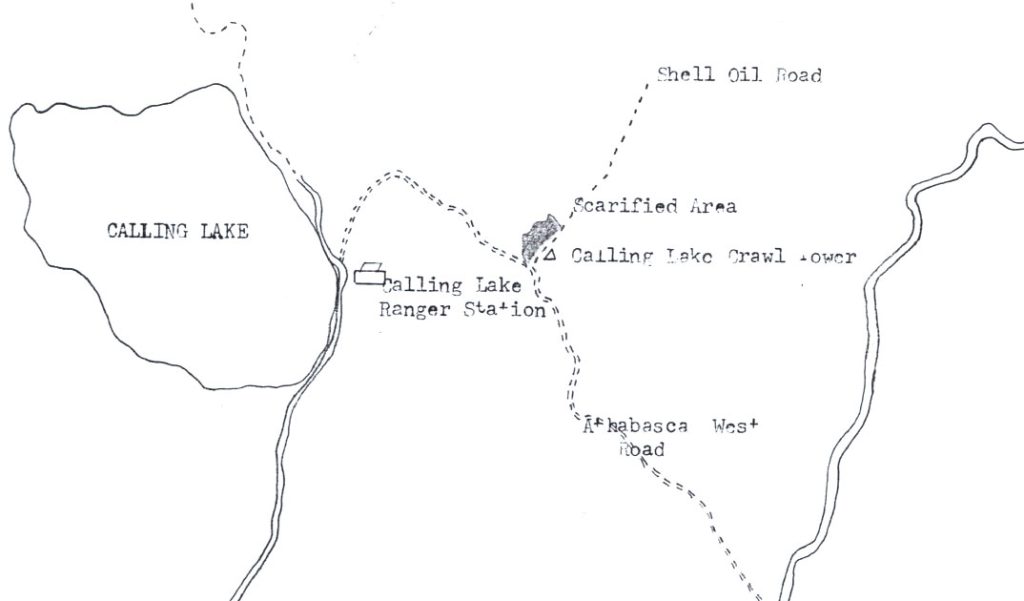

The Calling Lake Ranger Station was closed with centralization of government forestry offices in the mid-1990s. The Athabasca Forest Area office in Athabasca then managed the old Smith, Calling Lake, and Wandering River districts. Today, Calling Lake is part of the Lac La Biche Forest Area, with a wildfire base located at the old ranger station site.

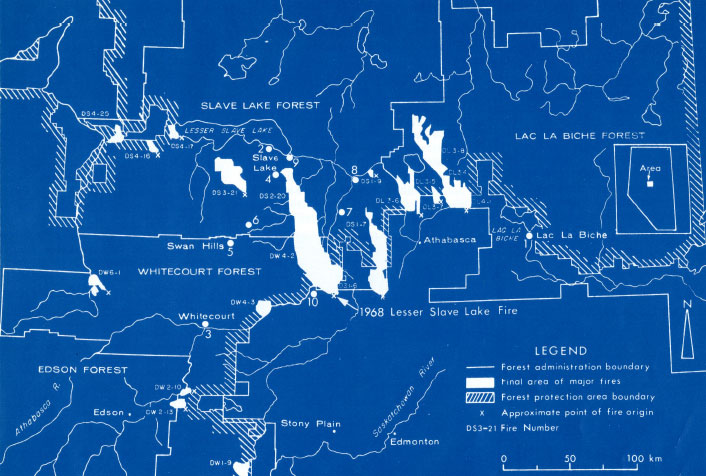

Wildfires

Alberta’s forests have been shaped by wildfires for centuries; the forests around Calling Lake are no different. While there were large wildfires in the late 1800s, the 1968 wildfires are the ones remembered from recent time. Windrow burning in the settlement areas along a line from Rocky Mountain House north to Whitecourt, Slave Lake and then east to Athabasca and Lac La Biche resulted in hundreds of wildfires. Of those,185 started between May 17 and May 25, 1968.

A number of wildfires burned in the Calling Lake area. These wildfires, all human-caused, originated from the settled area to the southeast. The largest one, spotting across the Athabasca River near the Lac La Biche River, threatened the community of Calling Lake when it burned east of the community to the northwest.

Firefighters having a lunch break at a staging area, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith

Firefighters having a lunch break at a staging area, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith Lunch break for Calling Lake firefighters, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith

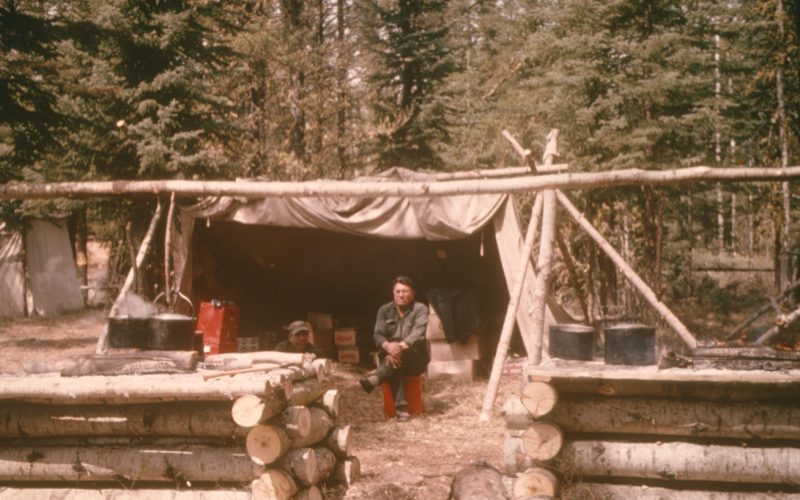

Lunch break for Calling Lake firefighters, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith Wildfire camp kitchen with log crib cooking fire, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith

Wildfire camp kitchen with log crib cooking fire, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith Firebase at the Calling Lake airstrip, May 1968 wildfires. Photo: Joe Smith

Firebase at the Calling Lake airstrip, May 1968 wildfires. Photo: Joe Smith Helicopter leaving wildfire base at the Calling Lake airstrip, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith

Helicopter leaving wildfire base at the Calling Lake airstrip, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith Calling Lake firefighters in the field, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith

Calling Lake firefighters in the field, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith Wildfire camp kitchen with log crib cooking fire, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith

Wildfire camp kitchen with log crib cooking fire, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith Fire camp at the Calling Lake forestry cabin and airstrip, with smoke in the air, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith

Fire camp at the Calling Lake forestry cabin and airstrip, with smoke in the air, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith Wildfire camp kitchen with log crib cooking fire, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith

Wildfire camp kitchen with log crib cooking fire, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith Calling Lake firefighters reviewing times or ordering commissary, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith

Calling Lake firefighters reviewing times or ordering commissary, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith Wildfire camp kitchen with log crib cooking fire, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith

Wildfire camp kitchen with log crib cooking fire, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith Calling Lake firefighters, battling May 1968 wildfires. Photo: Joe Smith

Calling Lake firefighters, battling May 1968 wildfires. Photo: Joe Smith Firefighter sleeping tents, Calling Lake airstrip, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith

Firefighter sleeping tents, Calling Lake airstrip, May 1968. Photo: Joe Smith

Reforestation

Maintaining Our Forests Program

Land Acknowledgement

Recognizing that we are all equally responsible to know our shared history and journey forward in good faith, we acknowledge with respect that Calling Lake stands on land, and alongside water, where Indigenous peoples have gathered, hunted, fished and held ceremonies from time immemorial.