Our Place in the World

Content

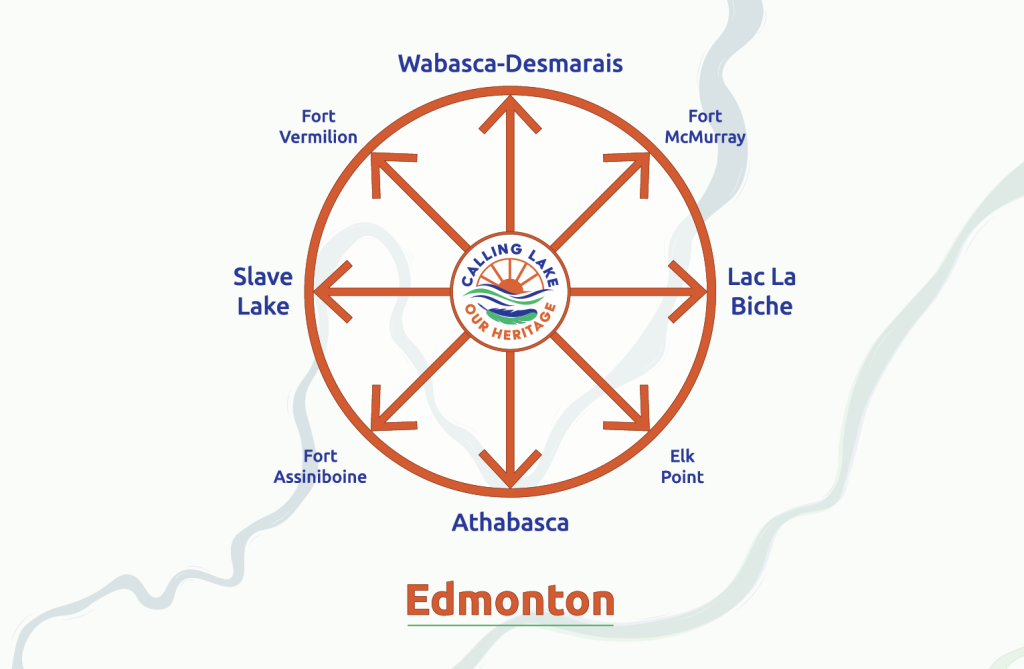

Imagine Calling Lake as the hub of a wheel whose outer rim extends north to the Arctic Ocean, northeast to the Hudson Bay, east to Manitoba, south into the United States and west beyond the Great Divide. That’s how we envision the area that has influenced who we are today.

Calling Lake is centrally located within that landscape. Situated at 55° 15′ 0″ North, 113° 12′ 0″ West, it lies midway between the US-Canadian border (the 49th parallel) and the Northwest Territories border (the 60th parallel); midway between Meridian 4, which runs along the Saskatchewan border, and Meridian 6, which cuts through the jagged BC border.

Within that larger ring are smaller rings containing communities with strong ties to Calling Lake, notably Lac La Biche, Fort McMurray, Wabasca-Desmarais, Fort Vermilion, Slave Lake, Fort Assiniboine, Athabasca and Elk Point. Those are the communities we focus on in more detail in our hunting and gathering, as they played huge roles in our development. Many of our forefathers came from or through them, whether by water or by land.

Most of those settlements were situated on major rivers, the liquid highways first travelled by Indigenous peoples and later by explorers and fur trade folks. Others hug smaller rivers that flow into the Athabasca. Those smaller rivers typically involved some overland portaging, at least in summer. Over time, early footpaths grew into horse and cart trails, evolved into rutted corduroy roads (named for the side-by-side logs used to fill in bogs) and were eventually graveled, broadened and (in some cases) paved. Along those pathways and more, folks found their way to Calling Lake over time, looking for a place to settle or simply get away from a life that was no longer right for them elsewhere.

The communities with strong connections to Calling Lake remain a big part of our story. To learn more about how people made their way around this landscape, see the suite called Modes of Transport.

Did you know?

Fort Vermilion

Located about 500 km north and a bit west of Calling Lake on the mighty Peace River, Fort Vermilion was inhabited by Dane-zaa (Beaver), Dene, and later Cree peoples long before Europeans arrived. An historic meeting place for northern peoples, it is named for the red clay lining area riverbanks. In 1788, the North West Company (NWC) established fur trading posts at Fort Vermilion and Fort Chipewyan, making them Alberta’s oldest European settlements.

After the NWC merged with rival Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) in 1821, Fort Vermilion became an HBC post. Well into the 20th century, the post was part of a major freighting route along the Peace River. Stretching from the Rocky Mountains east to the Mackenzie delta, the river’s many tributaries include the Wabasca River north of Calling Lake.

Today, most travelers reach Fort Vermilion by road, along Highway 88. The Fort Vermilion Heritage Centre helps to preserve the area’s history.

Fort McMurray

Now known for nearby oilsand production, Fort McMurray benefited in earlier times from its location at the confluence of the Athabasca and Clearwater rivers, then major transportation arteries for Indigenous peoples and those who followed. Beginning around 1786, a series of minor trading posts located here.

Then, in 1870, the Hudson’s Bay Company established a major post, named after Chief Factor William McMurray. As steamboats began moving furs toward Edmonton along the Athabasca River, the fort served as a major shipping terminal. The Alberta and Great Waterways Railway arrived in 1915, opening a new mode of travel, yet the population remained small until the mid-1960s, when oilsand production began to escalate.

Recent events impacting the community include a wildfire in 2016 and a flood in 2020. Learn more from the Fort McMurray Heritage Society website or by connecting with local author/historian Blair Jean and joining his Facebook group.

Athabasca

A small HBC post built then expanded during the 1880s to headquarter a network of steamboats that plied the Athabasca and other rivers. Both the Klondike Gold Rush and a lengthy visit by the Indian Treaty and Scrip Commission in 1899 stimulated growth. Then railways pushed north in 1912 and beyond, some bypassing Athabasca, and the area’s importance as a transportation hub diminished. The Athabasca Archives gathers evidence of the region’s history for all to use.

Other useful resources include Why Athabasca by historian Greg Johnson and Athabasca Landing: An Illustrated History by the Athabasca Historical Society.

Fort Assiniboine

Located at the confluence of the Freeman and Athabasca rivers, Fort Assiniboine was founded as a trading post by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) in 1824. Originally known as Athabaska River House and later named after the area’s Assiniboine people, the fort was the northwest end of an overland horse track to Fort Edmonton cut by Métis free trader Jacques Cardinal. This route was revived in 1897-1898 as part of the Chalmers Trail to the Klondike gold fields through Canada.

As in Calling Lake, several saw and lumber mills operated in the area as early settlers cleared land, built farmsteads and supplemented their income. Fort Assiniboine burned down after being abandoned, but the land on which it stood is now a National Historic Site and museum.

Elk Point

In 1792, Montreal-based North West Company (NWC) and rival London-based Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) established side-by-side forts a few kilometres below modern Elk Point on the North Saskatchewan River. For eight years, NWC’s Fort George and HBC’s Buckingham House traded metal goods, textiles, arms, ammunition, rum and tobacco for the coveted furs brought by Indigenous peoples – mainly Cree and Assiniboine but also Blackfoot, Peigan and even Blood and other groups from southern Alberta. Both forts also supplied great quantities of pemmican, the concentrated food used to nourish canoe brigades.

By 1800, with area fur resources nearing exhaustion, both forts moved further upstream. The fort sites became a Designated a Provincial Historic Resource in 1976. Local history is also kept alive by the Elk Point Historical Society, whose members are sharing what they know about the region with the Calling Lake history team.

Lac La Biche

There is evidence that Beaver, Sarcee, Sekani and Blackfoot peoples inhabited this area as far back as 8500 B.C. before being displaced by the Chipewyan and Cree peoples who predominate now. Aided by Indigenous people and Métis guides, North West Company (NWC) and Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) traders established posts at Lac La Biche between 1798 and 1799, and for a time “Portage La Biche” became part of a coast-to-coast water highway.

For the fur trade companies, the route through Lac La Biche to the Athabasca River was a critical transportation link until the area ran low on furs and resources and traffic moved further north. The Lac La Biche River flows into the Athabasca River very close to the Calling River outflow, but from the opposite side. As a result, paddlers between the two communities must go upstream one way or the other. Many have done exactly that. Case in point: Missionaries from Lac La Biche, a major Oblate mission and supply depot opened in 1953, were the first to bring the Catholic faith to Calling Lake. The mission is now a National Historic Site. You can also learn more at the Lac La Biche Museum.

Wabasca-Desmarais

Three bodies of water give Wabasca its name: North Wabasca Lake, South Wabasca Lake and the Wabasca River running between the lakes and beyond. The name “Wabasca” comes from the Cree word “wâpuskâu,” meaning grassy narrows, and “wâbiskâw,” meaning white caps. The Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) first opened a trading post in the Wabasca area in the 1880s, followed by an Anglican mission (1894) and Catholic boarding school (1901). The signing of Treaty 8, coupled with booming fur trade, brought more growth.

Wabasca also incorporates the historic community of Desmarais, which is named after Father Alphonse Desmarais, the first missionary there. The communities are surrounded by several reserves, and Wabasca is now headquarters for the Bigstone Cree Nation.

The Municipal District of Opportunity #17, which includes Calling Lake, is also headquartered in Wabasca. As in Calling Lake, early inhabitants likely arrived here via smaller rivers, including the Pelican River, which flows into the Athabasca River near Pelican Rapids. Both Wabasca and Calling Lake have families with roots in an early settlement located at Pelican Rapids.

Slave Lake

Slave Lake is not far from Calling Lake by winter road; folks traveled on the Little Slave River, which dumps into the Athabasca River at what was once Mirror Landing, now known as Smith. Over time, many trading and family developments have linked our two communities.

As in other northern communities, both the North West Company (NWC) and Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) were operating trading posts in the area by the early 1800s.For furs, they depended on First Nations in the area, predominantly Beaver and Cree.

In 1899, Treaty 8 received its first seven signatures on the banks of this lake, with the local Sawridge First Nation among the signatories. In the early 1900s, the Sawridge community (later called Slave Lake) became a stopping point for riverboats connecting Edmonton to the Peace River country via the Athabasca River.

The area boomed during the Second World War with construction of the Alaska Highway, and from the 1950s to 1980s with timber and oil resource development.

Learn more about the history of Slave Lake online or by connecting with Sheila Willis, whose writing about area history includes books on the Lesser Slave Lake Region and the online magazine Sheila’s Shenanigans.

Edmonton

Long a gathering place for Indigenous peoples, the Edmonton region saw numerous forts come and go along the North Saskatchewan River as rivals fought for supremacy in the fur trade. The North West Company’s (NWC) Fort Augustus, first built north of present-day Fort Saskatchewan in 1795, was soon countered by three other forts, most notably Hudson Bay Company’s (HBC) Fort Edmonton House just “a musket-shot” away. After several moves, the NWC and HBC amalgamated in 1821, and Fort Edmonton became administrative and supply headquarters for fur trade throughout the North Saskatchewan region. Eventually located below what is now the Alberta Legislature, the fort attracted trade from the Blackfoot to the south and the Cree, Dene and Assiniboine to the north.

As a key link in the system of trails that led across the prairies and into the mountains, Fort Edmonton had significant influence on developments in the north. The area’s history from Indigenous times is celebrated at Fort Edmonton Park.