Stepping through time

Content

Related Documents

The bounty and beauty of the body of water known as “Calling Lake” attracted humans as well as animals long before recorded history – perhaps from “time immemorial,” as Indigenous oral history says. This suite of rooms explores the broad sweep of the journey from those early times to the community of Calling Lake today – a mix of First Nations, Métis and settler households as well as cottagers living alongside the Jean Baptiste Gambler Reserve.

If you have any memories, photographs or artifacts to contribute, please contact the history committee.

Why Calling Lake? Origin of the name

The community of Calling Lake takes its name from the body of water that forms its backbone. First Peoples here call it ᑭᑐᐤ ᓵᑲᐦᐃᑲᐣ (Kitow Sâkahikan) or “the lake calls out” in Cree, a nod to the growling moans emitted as the ice breaks up each spring. Perhaps the sounds are caused by submerged gas pockets, or freeze-thaw cycles, or high water levels – or, according to legend, to the call of a maiden in a storm, lured to death by a spiteful spirit.

By A Lake of Sparkling Blue, A history of Calling Lake School by Dora Shwaga (1997) tells of several legends related to the name.

Legends related to the naming of “Calling Lake”

The name Calling Lake was given because of the “calling” sound that can sometimes be heard coming from the lake on a clear calm day. This recurring natural phenomenon has never been scientifically explained, but many legends have been told.

One legend tells that the sound is made by the ice when it freezes hard and is cracking.

Another legend tells of an Indian out in the middle of the lake, who calls for help because his canoe is capsized by a sudden storm. The same legend explains why the Indian people years ago would not travel directly across the lake, but would follow the lakeshore when they needed to reach the opposite side.

A historical survey of school districts compiled in 1927 for the Provincial Archives states: “Another story is that when the lake is high, whether in winter or in summer there is sometimes a sound like distant blasting.”

A fourth legend tells of a submerged gas pocket out in the lake bottom that creates this sound as the gas is released.

There are probably many other versions too, but my favourite is the following prize-winning essay written in 1944-1945 by June Davidson, a student in Cloe Day’s Grade 9 class at the Whitelaw High School in the Peace River area.

CALLING LAKE

By June Davidson

Of all the interesting people, places and things I encountered on my trip this summer, I think the most fascinating to me is the legend about Calling Lake and how it got its name. It is a beautiful spot about forty-five miles straight north of Athabasca, where they have no highway nor railway yet. There has been a settlement there, however, for years and years. It is a commercial fishing lake and good trapping country. A large part of its population descends from the Cree tribes of long ago.

My story is about the queer natural phenomenon that gives the lake its name and the Indian legend explaining it:

A long time ago when Payok Cryil’s grandfather’s grandfather was a very small boy, each Indian tribe had its guardian spirit. And if it was a very good tribe, the spirit would sometimes appear to one of its members to give advice or warning of danger.

The tribe that settled on this lake, and Payok’s grandfather’s grandfather among them (Old Payok tells the story and vouches for its truth because his grandfather told him and he had it from his grandfather), as I say, this tribe was particularly favored by all the spirits. Its men were brave and strong and wise; its women beautiful and clever with their hands. Their guardian spirit was very proud of his band and boasted to the other gods that no evil could enter into their hearts.

One wicked spirit who heard the boast became frightfully jealous. His tribe was nothing to boast about and e never received praises form the higher gods. He decided to bring some evil to the favored tribe or coax them into wicked ways.

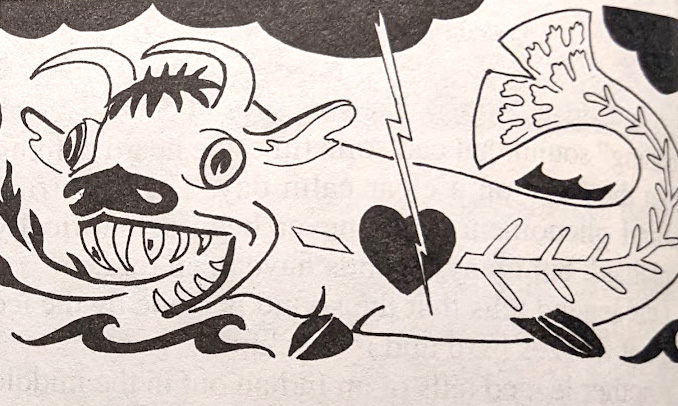

“Pesiskiniseeo” was the name of this spiteful spirit, and it meant “horrid fish-animal.” He could change himself into a dreadful monster, half fish and half beast, when he chose. The tribe’s guardian spirit was called “Assemin Kipahpin” or “giver of laughter.” He went to warn his people of the danger that Pesiskiniseeo would be to them. He appeared in a dream to the chief himself and said, “Beware the fish-beast! I can say no more. Th rest lies with your people.”

The chief called a council of all the tribe the next morning. When he told them of his dream the medicine men took council and explained its true meaning. All the warriors and their squaws made a vow to be ever on guard and not listen to the voice of evil.

Their vow was not an easy one to keep. At first Pesiskiniseeo appeared to them as a gay young chief and tried to coax them from their ways of goodness and fair play. They ignored him. Then he whispered secrets into their dreams. But they refused to be swayed by him.

At last he became vicious and appeared as the hideous monster he was, with a breath of fire and huge scabby tail that could throw a dozen warriors over at once. He threatened to destroy the tribe by degrees unless the people followed his laws for their future. It was a very trying time for the people and they were beginning to wonder if it would not be wiser to break their vow.

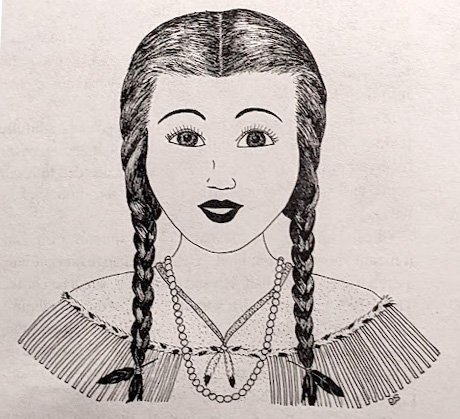

Now the chief had a lovely daughter, “Pasquou” or “The Beautiful,” who felt deep sadness over the plight of her father’s people. All night she could not sleep for thinking of the monster’s visit on the morrow. She stood at the door of her father’s teepee – a slim, willowy girl, with two long braids of jet black hair. Her eyes were like dusky pools in the moonlight and her teeth were little pearls behind lips of dark red velvet. She saw the stars twinkling up at her form the breast of the lake and the moon made a path of glory across its rippled surface. It seemed to be showing her the way.

“Yes,” she thought. “I will do it. It is the only way to save my father’s people.”

Early in the morning, Pasquou arose and dressed herself in her most beautiful robes of baby doeskin with ermine trim. She brushed her long black braids until they rippled like polished jet and clasped them back with the feather from a cardinal’s wing. Just as the autumn sun tipped the timberline to the east and threw its long rays to the shoreline of the lake, she stepped forth from the teepee and started slowly down the path to the water’s edge. Dewdrops glistened on the bushes beside her and the world seemed fresh and beautiful.

Just then, with a mighty rumble and roar, the monster flopped out of the forest and up to the village. All the Indians crowded into their wigwams and wondered what to do. The beautiful maid alone seemed unconcerned. She walked on to the shore and launched her canoe as if there was nothing at all out of place.

The evil spirit gazed at her in admiration and began to follow her with his flopping motions. She paddled straight out to the centre of the lake with the monster floundering behind her. Just before he overtook the canoe, a mysterious mountain of black smoke seemed to appear suddenly above them. Lightning flashed and thunder ripped through the quiet of the morning air. The monster hesitated and was turning back to shore. His beast head with its fiery breath must have air. A bad storm might overcome him and trap him.

Then the storm broke in a fury that the Indians had never seen before. The frail little canoe was dashed to bits almost instantly and the fiery monster sank between two huge waves and was never seen again.

And ever since that fateful day, especially in the autumn when the sun has risen red on a dew sparkling world, a listener may hear the deep rumble of the evil spirit’s voice rising from the centre of the lake. He is calling the tribe from his lair in the lake bottom, and no Indian will cross that lake to this day. If they must get to the other shore, they go around on foot or paddle their canoe all around the edge.

The white settlers there explain that distant booming sound on a clear day by various scientific possibilities. Some say it is gas in the bottom of the lake. Some say it is an electrical condition of the atmosphere above the lake. I have no theory to explain the queer calling sound, and I don’t believe I would offer it if I had. I like the legend of the beautiful Indian maiden sacrificing herself for her tribe, and I like the supernatural spirit the Indians give it. To me, the bad spirit of “Pesiskiniseeo” is calling for lost Indian souls

Our history in brief

Excerpted from Calling Lake Community Society Strategic Plan, 2021-2024

Thousands of years before explorers and settlers turned their attention to this area, Indigenous peoples visited the shores of Calling Lake. Studies carried out in 1964-1967 by Dr. Ruth Gruhn of the University of Alberta (Gruhn 1981) found evidence of early occupation at sites near the Calling River, on property owned by Ken Sutton. Researchers consider these sites characteristic of seasonal hunting or fishing camps. Calling Lake Elders recall an oral tradition that says First Nations people followed a migration pattern, living at Calling Lake for a time to fish off the lake and then moving to Rock Island to hunt.

The Calling River, which leaves Calling Lake at the southeast corner of the lake, meanders east until it discharges to the larger Athabasca River, connecting this area to a major waterway. This transportation corridor of the 1700s brought traders, settlers, missionaries and Indigenous peoples from the east. From established settlements such as Lac La Biche, they spread out to hunt, fish, farm and trade in areas such as Calling Lake. Some eventually settled here, running traplines, hunting and fishing, opening businesses, offering services, starting a school, building a community.

In the late 1800s, the federal government negotiated Treaty 8. Originally signed by the Woodland Cree at Grouard, it was later signed in other communities, including Wabasca (in 1899 by Chief Joseph Bigstone). The signing of the Treaty led to the establishment of several “Indian Reserves,” including Jean Baptiste Gambler Reserve at Calling Lake.

Journalist Charles Mair passed through this area in 1899 as secretary to the Métis Scrip Commission. He noted the need for an improved wagon road (“instead of the present dog-trail”) from Wabasca to Rock Island Lake, past Calling Lake and on to Athabasca Landing – a need that persisted for decades. He also described the Commission’s stop at the mouth of the Calling River, one of the places where scrip payments were distributed to those identifying as Métis, and of meeting one of Calling Lake’s oldest inhabitants, Marie Rose Gladue. Mr. Mair remarked that the common language spoken at that time was mostly Cree with a bit of English and French.

After Alberta became a province in 1905, the area northeast of Lesser Slave Lake, including Calling Lake, was placed under the administration of Improvement District 17 East (North). In 1995, it was incorporated as the Municipal District of Opportunity.

In the late 1950s, the government opened Calling Lake to “cottagers.” Lots were drawn for and developed over the next 10 years or so. As the municipality developed and as land was made available by various means, it became possible for more people to stay, and the community started to take on the character as we know it today.

Approximately 500 people live in the municipal district full-time, another 250 live on the Jean Baptiste Gambler Reserve, and the part-time cottager population is close to 2,000.

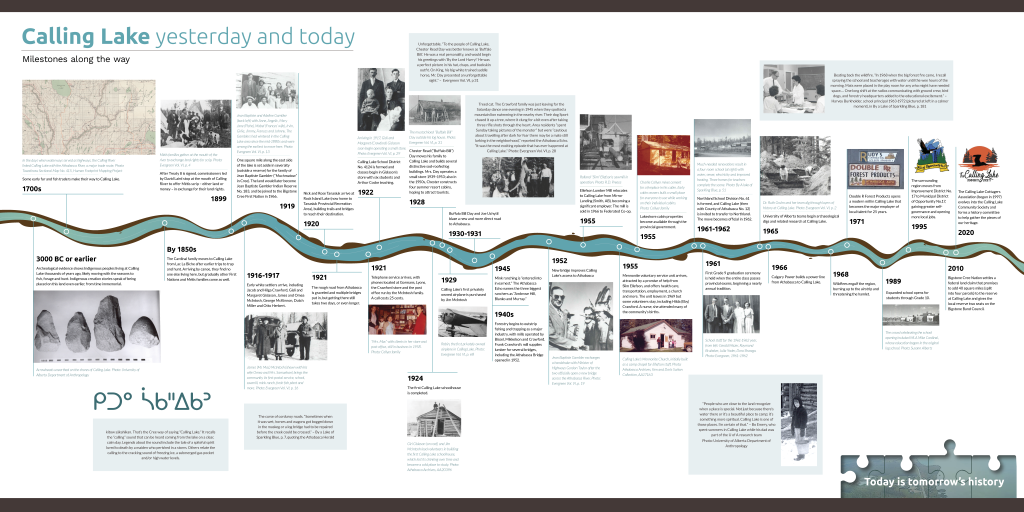

A short “river of time”

The following “river of time” draws from our initial research into Calling Lake history. We are already adding entries, with particular focus on long past and Indigenous people and events. If you have an entry to suggest, please contact the history committee.

Adding to the timeline

As we hunt and gather, a more comprehensive timeline of Calling Lake history is taking shape. If you have an entry to suggest, please contact the history committee. We are searching for information about all pieces of the puzzle, but especially about the earliest days, including times known mostly through Indigenous oral history.

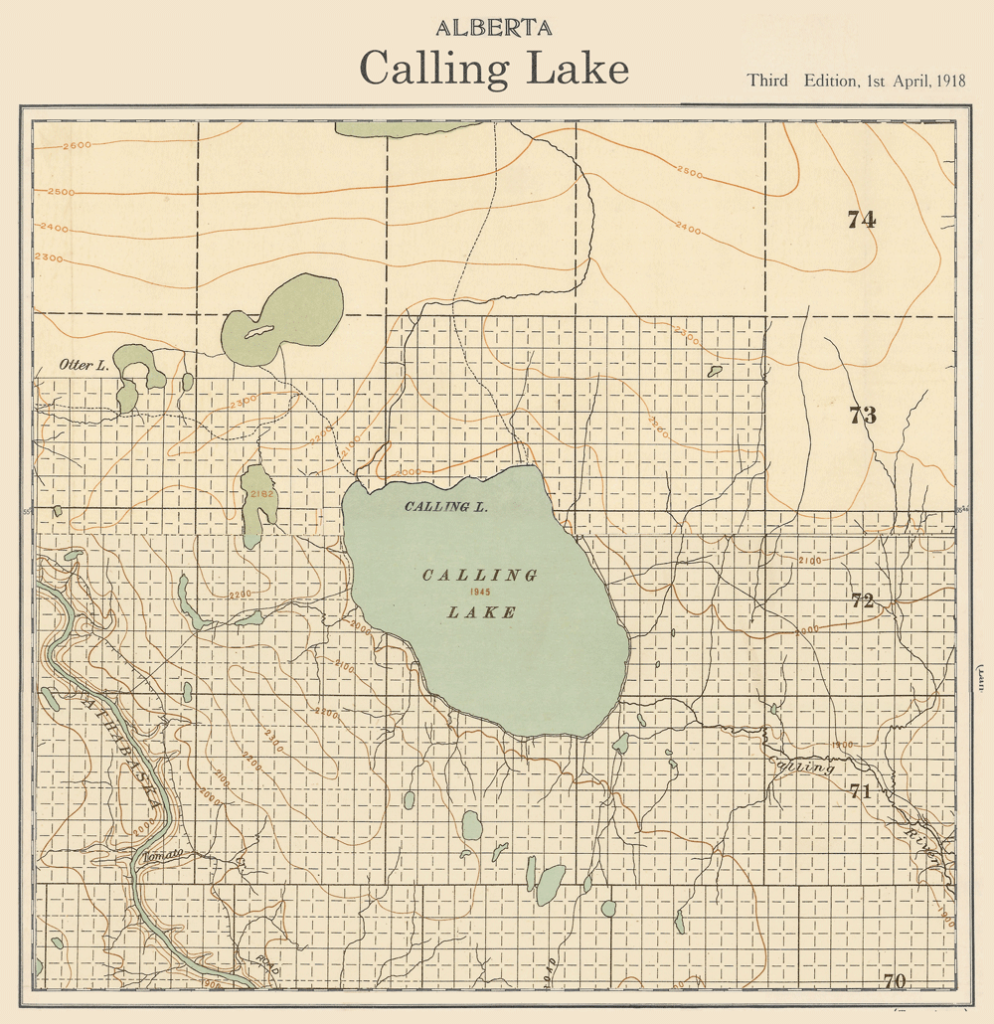

Historic maps of Calling Lake

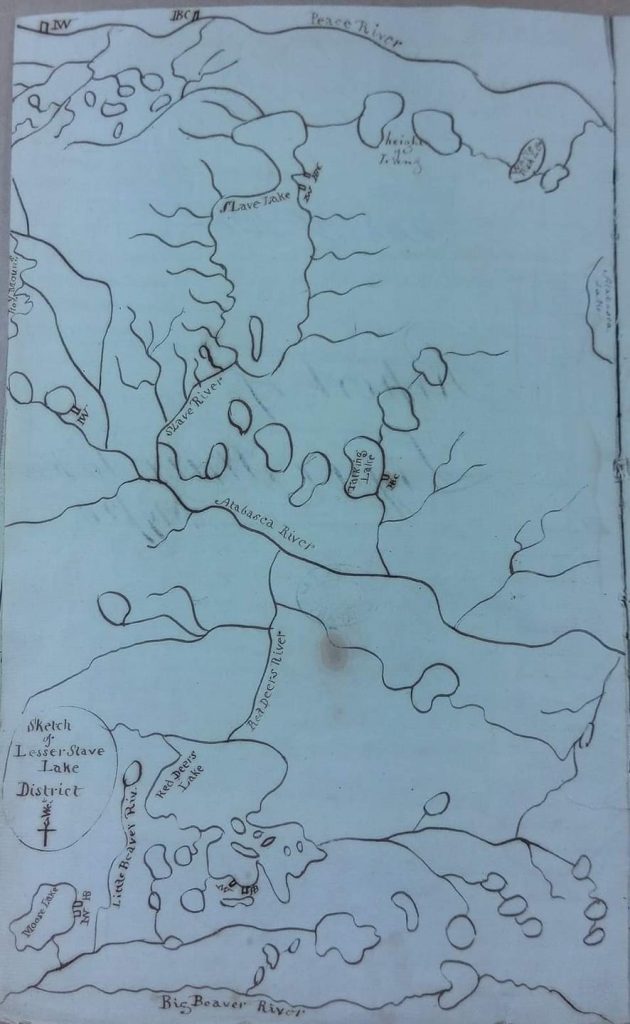

This map, likely drawn by Peter Fidler in the early 1800s, names the body of water we know as Calling Lake by another name: “Talking Lake.” Curious! Note also the HBC label by the lake, indicating a Hudson’s Bay Company post. This map came to us from Blair Jean, who with Allison McKinnon has written extensively about the history of the Clearwater River watershed. Someone posted the map on Blair’s very informative “Blair Jean Author Historian” Facebook page, and he kindly passed it on.

We shared the map with Mark Lund, another great friend of Calling Lake History Gathering, and he passed it to Andreas Korsos, who has carefully studied maps of historic fur trading posts. Korsos responded that he has found no record of a post at Calling Lake, but that short-lived outposts were common as the HBC and rival North West Company played hopscotch in pursuit of furs. Korsos adds: “I would suspect that if there was a post at Calling Lake it was seasonal and likely of not long life.”

Every answer raises another question. Have you ever heard that Calling Lake was once called “Talking Lake” – or that the HBC set up a post here? If so, contact us.

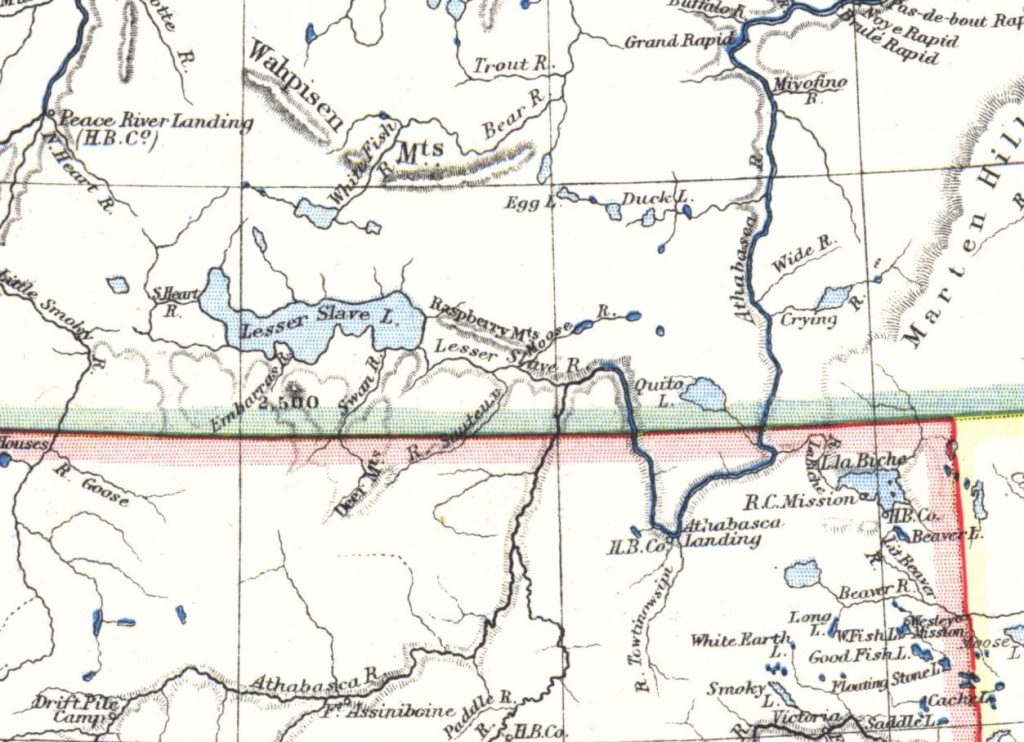

In this 1885 map, posted at docs.google.com, the lake we know as Calling Lake is labeled “Quito Lake.” Sheila Willis, who has also done extensive research and writing on this region, notes that this map also spells Saulteaux River in an unusual way, adding “I suspect he was making his map by lamplight or he was writing based on his own language accent, or he needed glasses.”

Sheila Willis also notes that Calling Lake is called “Echo Lake” in Through the Mackenzie Basin, a journal kept by Charles Mair while traveling with the 1899 Treaty Commission, which made a stop near Calling Lake, at the Calling River. A Cree word for “Calling” or “Echo” is “Kito.” Perhaps that helps explain the label “Quito Lake.”

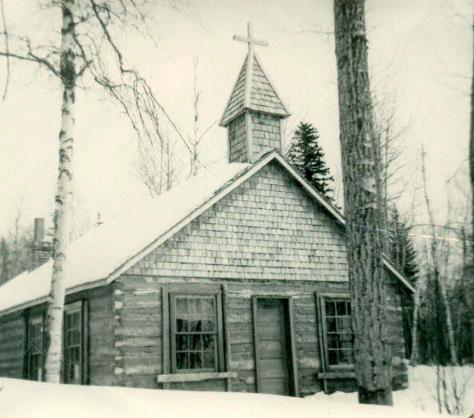

Heritage sites & signs

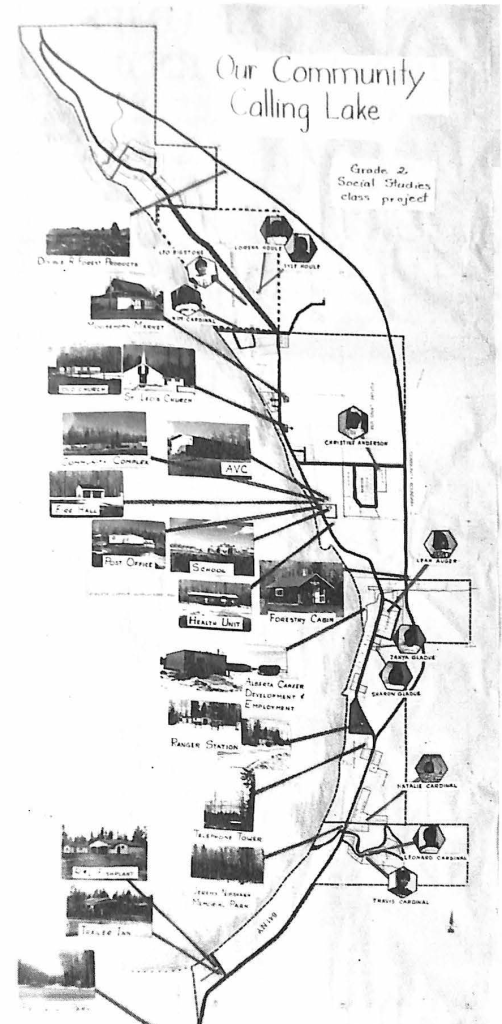

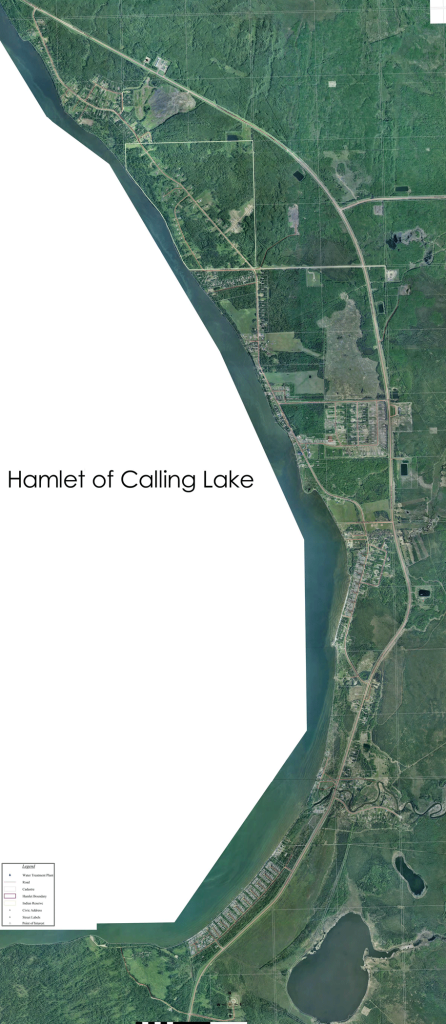

Calling Lake today

Now part of the Municipal District of Opportunity No. 17, Calling Lake is home to a blend of Indigenous, settler and cabin households. About 500 people live in the hamlet full time, another 250 live on the Jean Baptiste Gambler Reserve (part of the Bigstone Cree Nation) and nearly 2,000 are cottagers who come here part time.

Located immediately north of Calling Lake Provincial Park along Highway 813, Calling Lake is about 59 kilometres north of Athabasca and 113 kilometres south of MD headquarters in Wabasca. Services include the J.B. Gambler Store, opened in 2022 on the reserve, and Moosehorn Market, which has passed through several hands over the decades. Interpretive signs in parks and at the Interpretive Centre at the heart of the community provide glimpses of the area’s past.

The community hugs the eastern shore of Calling Lake, long known for its beauty and bounty of fish. Opportunities to explore this scenic region include Calling Lake Provincial Park and day-use areas such as Jeremy Nipshank Park and Ben Auger Memorial Park.

Find out more about Calling Lake today at Community.

Land Acknowledgement

Recognizing that we are all equally responsible to know our shared history and journey forward in good faith, we acknowledge with respect that Calling Lake stands on land, and alongside water, where Indigenous peoples have gathered, hunted, fished and held ceremonies from time immemorial.