Expressions of Faith

Content

Related Documents

Indigenous Spirituality

The spiritual beliefs carried forward by Indigenous peoples from generations past vary widely, as do contemporary beliefs and cultural practices. Yet commonalities exist among Indigenous spiritual traditions, including the presence of creation stories, humanity’s interconnectivity and need to balance with nature, the role of tricksters or supernatural beings and the importance of sacred organizations and rituals. Traditional activities and ways of life, such as hunting and feasting, are often infused with spiritual meaning. Examples include the Wihkohtowin (ritual feast) described below and the understanding that Memeguayiwahk (little people) live in caves and sandhills along water bodies. We have heard that little people lived along the Calling Lake riverbank, near what are now the cultural grounds, but since Indigenous people have moved from there the little people have as well.

We are seeking the guidance of community elders to correct and add to the few descriptions and examples of Indigenous spirituality included here.

A Composite Description of the Wihkohtowin

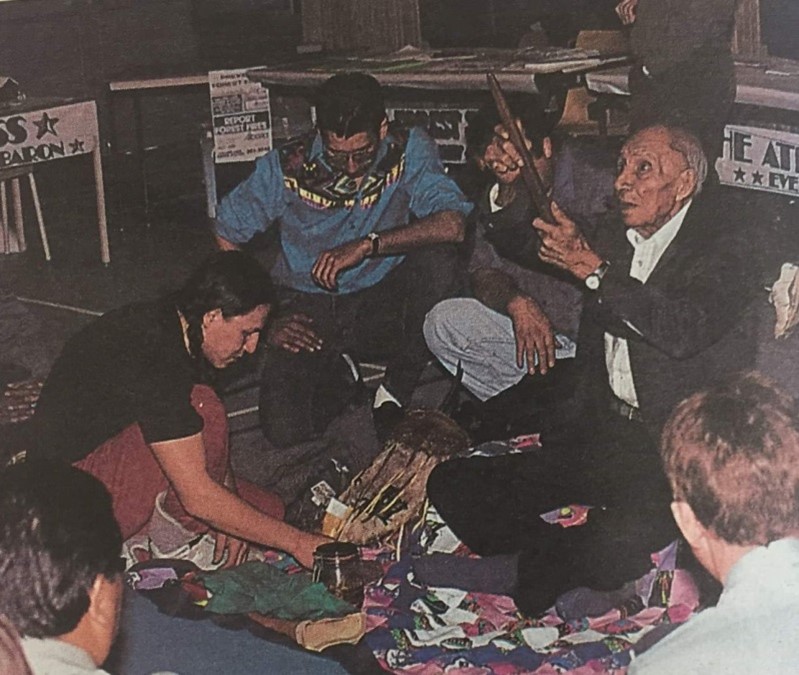

The wihkohtowin combines dancing, feasting, sacrificing, singing, drumming, praying, gifting, blessing and healing. The ritual was widely undertaken in spring and fall (also perhaps in midsummer, as some of my informants suggested), at important seasonal gathering sites. It was a major feature of social life, building solidarity among small bands throughout the season of their largest gatherings. It continues to serve an integrative function by honouring relations to ancestors and the spirit world, blessing medicines and sacralizing items of personal power such as bundles, bringing them into the rhythm of the seasons and of plant life. Apart from its seasonality and relation to plant life, the ceremony ties into the rhythms of the universe in other ways, in that the dancers’ movements mimic the sun, the ritual is frequently held at the full moon and the ceremony typically starts at sundown and ends at sunrise. In these respects, both the contemplation and practice of the wihkohtowin tend toward and evoke circular, recursive and self-referential symbolism of a primal nature.

The main part of the ceremony consists of dancing, typically around four fires, in a clockwise direction and in single file in the wihkohtowikamik, an oblong lodge constructed from multiple conical teepee frames, partially covered with canvas or boughs but open across the top, save a transverse pole. The door faces east or south, with the altar, the area where the drummers sit, opposite. Another fire burns outside the lodge, for those who need a break from the intense ritual or for those who are restricted from entering, such as menstruating women, which is consistent with a range of menstrual taboos in subarctic societies. The lodge is strongly associated with the ceremony, structuring it spatially into more and less sacred zones. The poles themselves have a special significance, as different trees represent community members of different age and sex statuses. The transverse pole with its greenery represents the spiritual leadership of the elder. The lodge represents the community prayerfully coming together to support future generations. In most cases, men and women sit together in families, while in some cases they sit separately….

The ceremony opens with invitational drumming and prayerful invoking of the spirits—generally identified as the spirits of the dead but sometimes as animal spirits—to enter the oblong lodge and share in the feast. There may be six or eight drummers who take turns playing eight rounds or more. This ceremony can last most of the night or even consecutive nights and often involves multiple meals. It is considered critical that people eat as much food as possible. As not all the food is always consumed during the ritual, the remainder is typically put in the fire, eaten in the morning or covered to be taken home.

Mike Beaver emphasizes that the Creator (kihcimanitow) is ultimately the target of the prayers said in his lodge. Prayers could also be directed at animal spirits, to the four directions and to other spiritual grandfathers and grandmothers. Eddie Birdtail referred to this (in response to a question about the role of animals in the ritual during our interview at Trout Lake, October 2013), saying, ‘‘The ceremony is for the animal! They thank the animals, spirits, people who passed on. Like,he [the ceremonialist] invited them.’’ In many such descriptions, the spirits of animals and ancestors, among other entities, appear to be closely associated with one another as beneficiaries of the sacrifice. The ritual is thus situated in relationship to the environment, not only the terrestrial environment but also the cosmos.

…. Like the rituals of the hunter, who disposes respectfully of animal parts and makes burnt offerings, the wihkohtowin exemplifies the reciprocal relationship of spirit gifting (Ghostkeeper 1996). The gift goes beyond the eaters, as the food nourishes absent and deceased kin. The ceremony feeds a collectivity of past and future people while, in some analyses, also welcoming the animal spirits into that community, the commensal domus that is the lodge.

Little People, Ma-ma-kwa-se-sak or Memeguayiwahk

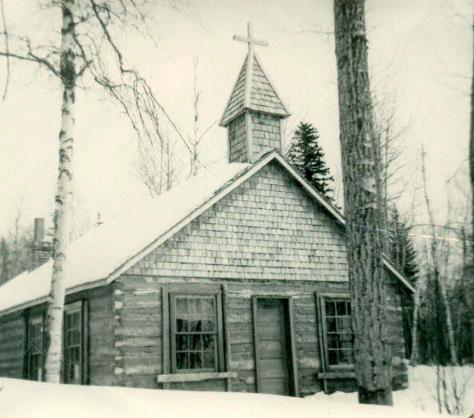

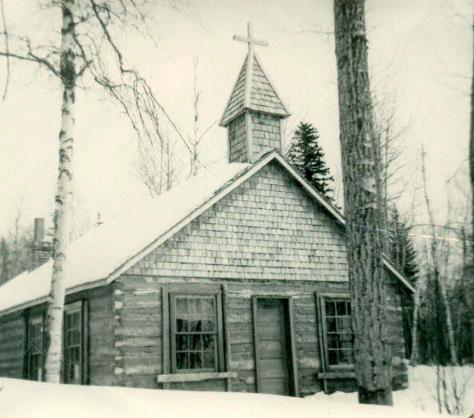

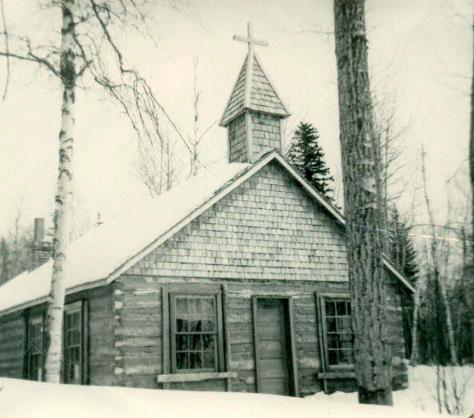

The Church of St. Léon le Grand

Thanks to the Kito Sakahekan Seniors Society, and especially Av Mann, we have an account Calling Lake’s first Catholic Church in the book titled The Church of St. Léon le Grand: A History of the Catholic Church and Early Families of Calling Lake, Alberta. The book describes the congregation’s beginnings this way:

The Roman Catholic Church, as a physical entity, came rather late to Calling Lake. The first church building was not completed until 1948, and this not blessed until 1951. To the south, a Catholic church had been established at Athabasca in 1891 – half a century earlier – although it had no permanent staff until 1905. To the north, Father Alphonse Desmarais was the first Catholic missionary in the area known today as Wabasca-Desmarais, arriving in 1891. Reverend J.B. Giroux established a permanent mission at Wabasca in 1896.

Although a permanent structure was lacking, this is not to say there were not efforts to service the Calling Lake area prior to 1948. According to the Athabasca Herald, Jean Baptiste Gambler married his wife Adelaide Mayas (daughter of Jean Baptiste Mayas and Marie Anne Misinisikapaw) in Calling Lake in 1903. They were married by Oblate J. B. Giroux who had also baptized Adelaide in Calling Lake in 1890. This event, and others like it, would have taken place in local Calling Lake homes.

In 1908, Reverend Pétour, based at Wabasca, attempted to build a church at Calling Lake beside the cemetery. However, his efforts were destroyed by a W. Webbs, who owned land adjacent to the proposed church site. No other explanation of this dispute survives today. Priests from the Wabasca area or from Smith continued to provide services to the community.

Church resources were likely another reason for the delay in establishing a permanent base in Calling Lake. In 1905, the official status of the Catholic Church in Canada and the United States was changed from being a “mission” church, and thus receiving funding for its operation, to being an “independent” church having to finance its own operation. This change presented great difficulties in many areas. Additionally, with the cathedral built at McLennan in 1946, local church resources were likely strained. Nonetheless, in 1941, Bishop Langlois gave Reverend Guimont, then stationed at the mission in Wabasca-Desmarais, approval to build a church of “squared off logs” at Calling Lake.

One can only speculate, but presumably these funds helped to pay for the construction supplies required for the chapel to be built at Calling Lake the following year. The Church had already acquired the land many years previous. Although details vary, the story goes that Benjamin Cardinal and his son Clopheus filed, or applied, on the 1/4 section on which the church now stands. Clopheus had five children when his wife died. He then remarried a widow who also had five children. The widow had Treaty rights so her children could attend the mission residential school at Wabasca. Clopheus was non-Treaty, however, so his children were not eligible. Clopheus wanted his children to attend school, so he provided land for a church in Calling Lake in return for the Church accepting his children into school.

At some point after the blessing took place in 1951 (but before Father Habay visited in 1962), a church bell was acquired and this addition required some modifications. Francis Cardinal can remember how heavy the bell was. Although it has since gone missing, it was probably very similar to the bell on the current church, which is cast iron and made in the late 1880s by the C.S. Bell and Company of Hillsboro, Ohio. To accommodate this weight, the cupola was removed and replaced with a bell tower, which also added a new entrance way (portico).

At some point after the blessing took place in 1951 (but before Father Habay visited in 1962), a church bell was acquired and this addition required some modifications. Francis Cardinal can remember how heavy the bell was. Although it has since gone missing, it was probably very similar to the bell on the current church, which is cast iron and made in the late 1880s by the C.S. Bell and Company of Hillsboro, Ohio. To accommodate this weight, the cupola was removed and replaced with a bell tower, which also added a new entrance way (portico).

Over the years, various repairs to the church were made. At some point, the bell tower was again removed and the cedar shakes on the gable ends were replaced with carefully scalloped, vertical boards. Other modifications likely occurred but the essential character of the original building has remained.

The old Catholic Church at Calling Lake was never staffed full time. Priests from Wabasca or Smith, travelling by dog sled in the winter and horse by summer, came up from time to time to perform needed services including weddings, christenings and funerals. At first, these services were performed in people’s homes. Later on, they were performed in the little log chapel.

Activities in the church included all the usual things that occur in a community. Children were baptized, couples were married, and the deceased were given prayers and buried. At some point, Catechism classes were conducted by the Reverend Sisters and a group of local children were given their First Communion in the log church. The Calling Lake community was also part of a larger Catholic community and several Calling Lake residents also travelled to events such as the Lac Ste. Anne pilgrimage.

As progress came to Calling Lake, the church adapted as well. In 1962, Reverend E. Fournier became the first resident Roman Catholic priest at Calling Lake (Fall 1962 – Spring 1966). Perhaps to better house his congregation, the Reverend constructed a new church at Calling Lake.

This church is immediately south of the old log church and was blessed by the same Bishop (Bishop Routhier) in 1963. The new church was first used for worship on the Feast of Christ the King, October 25, 1962.

One can only speculate, but presumably these funds helped to pay for the construction supplies required for the chapel to be built at Calling Lake the following year. The Church had already acquired the land many years previous. Although details vary, the story goes that Benjamin Cardinal and his son Clopheus filed, or applied, on the 1/4 section on which the church now stands. Clopheus had five children when his wife died. He then remarried a widow who also had five children. The widow had Treaty rights so her children could attend the mission residential school at Wabasca. Clopheus was non-Treaty, however, so his children were not eligible. Clopheus wanted his children to attend school, so he provided land for a church in Calling Lake in return for the Church accepting his children into school.

In 1944, building specifications approved by the Church were provided to the Tanasiuk brothers, Jim and Mike, and a contract for $200 was signed. That winter, the brothers felled and skidded the logs to the building site and stripped off the bark with long knives. The logs were then left to dry. Eventually, the logs were hewn into the desired length, shaped by hand with broad axes and construction begun.

On Oct. 10, 1947, the small chapel was completed. It was a modest one-room square-log structure lacking any amenities like indoor plumbing but likely heated by a wood stove and a good supply of firewood. Some care was taken to complete some of its finer details like the dove-tail log ends, the cupola bearing a wooden cross, and the wooden shakes covering the cupola and gable ends. Both the inside and outside were chinked and six windows were installed.

At some point after the blessing took place in 1951 (but before Father Habay visited in 1962, a church bell was acquired and this addition required some modifications. Francis Cardinal can remember how heavy the bell was. Although it has since gone missing, it was probably very similar to the bell on the current church, which is cast iron and made in the late 1880s by the C.S. Bell and Company of Hillsboro, Ohio. To accommodate this weight, the cupola was removed and replaced with a bell tower, which also added a new entrance way (portico).

Over the years, various repairs to the church were made. At some point, the bell tower was again removed and the cedar shakes on the gable ends were replaced with carefully scalloped, vertical boards. Other modifications likely occurred but the essential character of the original building has remained.

The old Catholic Church at Calling Lake was never staffed full time. Priests from Wabasca or Smith, travelling by dog sled in the winter and horse by summer, came up from time to time to perform needed services including weddings, christenings and funerals. At first, these services were performed in people’s homes. Later on, they were performed in the little log chapel.

Activities in the church included all the usual things that occur in a community. Children were baptized, couples were married, and the deceased were given prayers and buried. At some point, Catechism classes were conducted by the Reverend Sisters and a group of local children were given their First Communion in the log church. The Calling Lake community was also part of a larger Catholic community and several Calling Lake residents also travelled to events such as the Lac Ste. Anne pilgrimage.

As progress came to Calling Lake, the church adapted as well. In 1962, Reverend E. Fournier became the first resident Roman Catholic priest at Calling Lake (Fall 1962 – Spring 1966). Perhaps to better house his congregation, the Reverend constructed a new church at Calling Lake.

This church is immediately south of the old log church and was blessed by the same Bishop (Bishop Routhier) in 1963. The new church was first used for worship on the Feast of Christ the King, October 25, 1962.

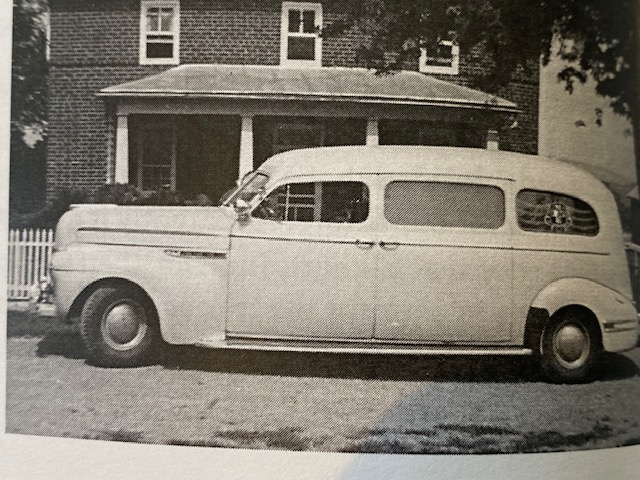

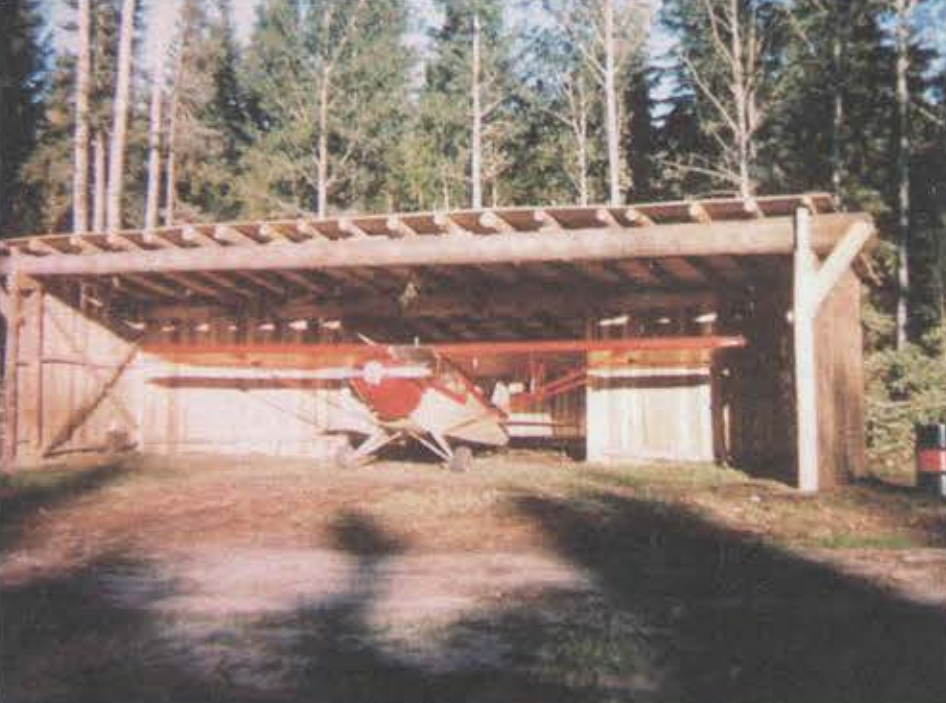

Mennonite Voluntary Service Unit

Between 1955 and 1969, a Mennonite Voluntary Service Unit set up headquarters in Calling Lake, attracted by a promise of help from Slim Ellefson. The Ellefsons were moving their sawmill to Calling Lake, which did not have a Protestant church then, and hoped the Mennonites would offer a worship community for their extended family. (Watch our Forestry room for more about Ellefson sawmill history.)

Responding to community need, the Mennonite volunteers’ work expanded over time to encompass health care, transportation, employment, a church and more. Some volunteers remained after the unit left and blended into the community. Among them was Hilda (Eby) Crawford, a nurse; for decades, she attended many of the community’s births.

Ike and Millie Glick, who led the service unit in the early days, have written a book about the experience, aptly named Risk & Adventure. Click here for a summary of the book, augmented by recent interviews with Ike.

Risk & Adventure: Community Development in Northern Alberta

Members of the Mennonite Voluntary Service Unit compiled a binder of memories fifty years later, when they gathered for a reunion. To read about other volunteers who served at Calling Lake, click on MVS 50th anniversary binder – Calling Lake.

Calling Lake Community Church

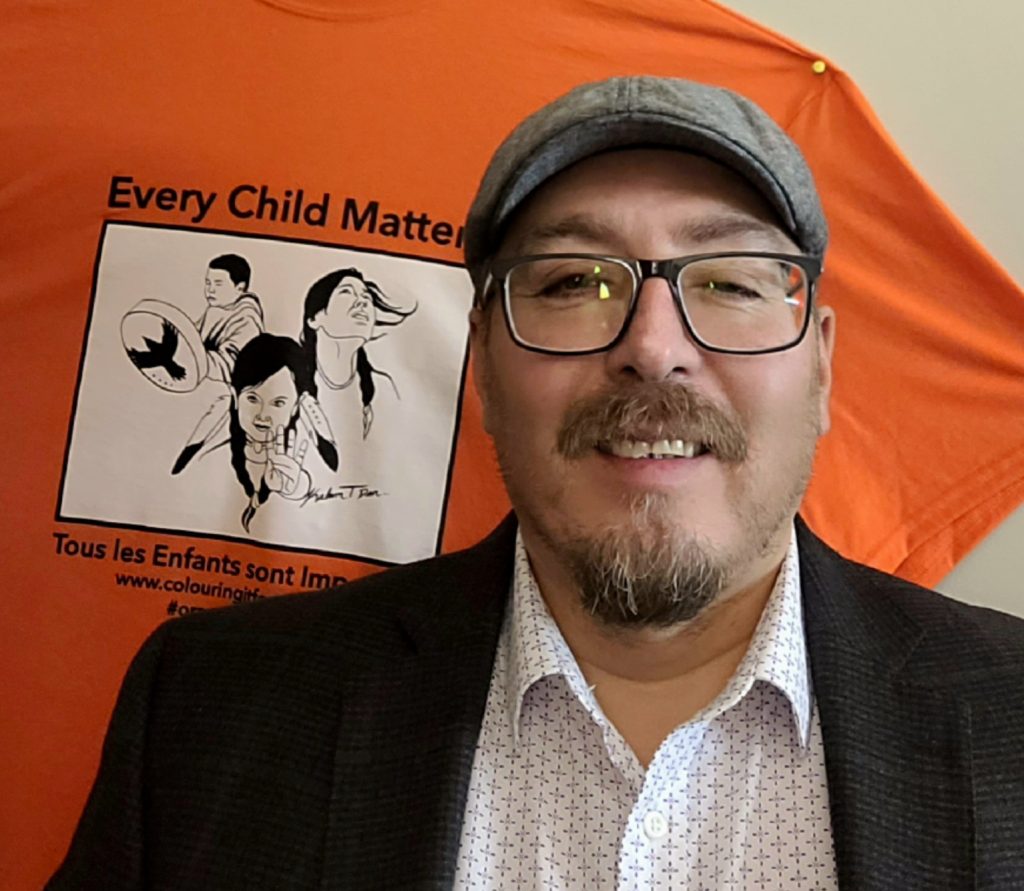

Another church active in Calling Lake today is Calling Lake Community Church, led by Pastor Nathan Gullion. In January 2022, the Calling Lake Community Health Services building was purchased to serve as both church and community centre. Following renovations, the congregation began worshipping there in May 2022. Previously, they were meeting at the Jay-Bird Arena and Recreation Complex, at no cost.

The church grew out of a Sunday School and Vacation Bible school ministry begun by the Athabasca Reformed Church in 1998. By 2014, the Athabasca congregation was hiring a youth and outreach workers to run programs in Calling Lake. Nathan Gullion joined the team in 2019, first as a student seminarian and now as full-time pastor.

Gullion grew up with an alcoholic father and ended up travelling the dark road of addiction, despair, homelessness and imprisonment before going to Taylor Seminary and finding his place in ministry. “I was a very troubled individual,” he says.

A member of the Bigstone Cree Nation, Gullion’s ministry includes food deliveries, transportation and lots of listening, in a way that merges traditional Indigenous ways with Christianity. “I play drum music, I burn sweetgrass, it’s a little bit more informal,” he says. He also uses his own story to counsel others battling similar demons, including drugs and alcohol. As he puts it, “I can tell you with all certainty, you can actually live a fulfilled life without all of that.”

For recent and upcoming events, see the Calling Lake Community Church Facebook group.